- Format: MP3

An early member of Fleetwood Mac, slide guitarist Jeremy Spencer left behind a fine (if limited) musical legacy, but is perhaps better remembered for his sudden defection from the group to join a religious cult. Spencer was born in West Hartlepool, England on July 4, 1948; he started taking piano lessons at age nine, switched to guitar at 15 to emulate his rock & roll idols, and the following year discovered Elmore James, who became his chief influence. In 1967, Spencer became the fourth member of the fledgling Fleetwood Mac, concentrating primarily on slide guitar but also doubling up on piano. He was a major component of the group's early blues-rock sound on albums like 1968's Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac and 1969's English Rose. A gifted musical impressionist, Spencer's affectionate send-ups of early rock & roll styles and artists were sometimes incorporated into the group's live shows; in 1970, Spencer released a self-titled solo LP in that vein on Reprise, featuring parodies of rockabilly, teen idol ballads, surf, Elvis, psychedelia, and even Mac itself. That same year's Kiln House would prove to be the last Mac album Spencer played on, however.

In early 1971, hours before the Los Angeles gig on Mac's American tour, Spencer vanished without warning; five days later, police traced him to the headquarters of a Christian sect called the Children of God, which Spencer had apparently joined after being approached on the street. Always somewhat religious, Spencer later revealed that he'd been feeling spiritually unfulfilled in the wake of the group's success; nonetheless, his abrupt departure left the group in a lurch. Not only did they have to call upon the unstable Green (who'd left a year earlier) to complete the tour, but in Green's absence, Spencer had been the main link to Mac's blues-rock past, which sent them into an identity crisis that wouldn't be resolved for several years.

Meanwhile, Spencer re-emerged in 1973 with a new album, Jeremy Spencer & the Children, on CBS; influenced by psychedelia and folk-rock, it was wholly devoted to Spencer's newfound faith. In 1975, Spencer returned to London and formed a blues-rock group called Albatross, which featured other Children of God; in 1979, he released another solo album on Atlantic, titled Flee. Though Spencer remained silent on record, he continued to play music and tour, and devoted much of his time to charitable causes. As the millennium drew to a close, Spencer toured India three times (in 1995, 1998, and 2000), worked on material for an instrumental album, and remained an active member of the Family (as the Children of God were later called). Then, suddenly in 2006, after a 30-year-plus absence from the recording studio, Spencer resurfaced with a new album on Blind Pig Records, the impressive Precious Little (the album was licensed from Norway's Bluestown Records, which originally released it), suggesting that Spencer's musical story was far from over.

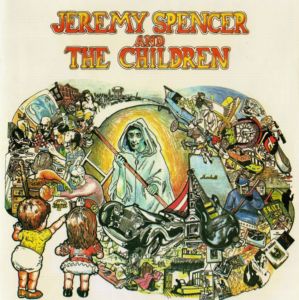

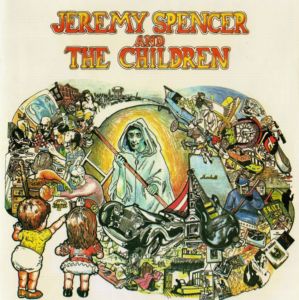

This 1972 release by ex-Fleetwood Mac guitarist Jeremy Spencer with his religious group the Children is as consistently good as the work by other members of that venerable band: Danny Kirwan's 1979 effort Hello There Big Boy, Christine McVie's 1969 recordings re-released in 1976 as The Legendary Christine Perfect Album, Bob Welch's Man Overboard from 1980, and In the Skies by Peter Green. These enormous talents should have somehow been able to shuffle a new combination/working relationship, or subbed with the real deal when Mick Fleetwood put a tour together sans Lindsey Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, and McVie; listening to these amazing discs it becomes clear that the public needed the trademark in order to hear what's in these grooves - none of these albums garnering success on the same level as Fleetwood Mac. The album that may have suffered the worst fate is Jeremy Spencer & the Children - this elegant "psychedelic Christian music," which in itself is a paradox. Phil Ham and Spencer's guitar playing is superb, the instruments singing with melodies and fragrances that are at some points breathtaking. The record works better than the band live, containing power that didn't translate well in the downstairs of Boston's Kenmore Club in the early '70s. It shimmers from the vinyl decades later, "Beauty for Ashes" a sweeping and precise essay with folk guitars embellished by the electric guitarists' immaculate leads. Did the religious overtones stunt the potential popularity, or was the presentation a little too "out there" for the record-buying public to grasp? The cover has a figure of death surrounded by material goods: television, guitar, amplifer, a swank car, tons of "things." This is so much like a Jefferson Airplane doppelgänger that it is frightening - or amazing. Ham adds lead guitar, flute, and sitar, while it is Spencer on slide guitar, piano, and vocals. "War Horse" is powerful: "Another young man dead/But who gives a damn/Those generals on Wall Street/Got control of our land." Paul Kantner must have approved of this big-time, the song sounding like latter-day Airplane musically veering off into Jethro Tull territory. The album is a combination of British and American styles, but its psychedelic/folk leanings are the dominant sound, with remarkable harmonies and a pristine production, as well-crafted as it was badly marketed. It is an impressive work, and possibly the most forgotten solo recording from a member of Fleetwood Mac.