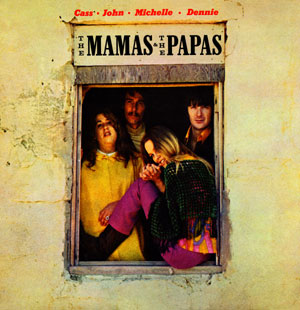

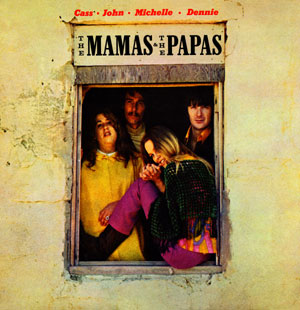

Sometimes art and events, personal or otherwise, converge on a point transcending the significance of either -- a work achieves a relevance far beyond the seeming boundaries of the creation at hand. During the 1950s and 1960s, in music, it used to happen occasionally for Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and Bob Dylan, once or twice for the Byrds, and a few times for the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones. For the Mamas & the Papas, it happened twice, with their first album, If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears, and, on a more complex level, with this album -- which was astonishing, given that they had a major upheaval in their membership in the midst of recording it. The Mamas & the Papas (also sometimes referred to as "Cass- John-Michelle-Denny," which might well have been the official title until that lineup started to shift) was recorded over a period of almost four months, in the wake of the massive success of their first two singles and the debut album, issued in February of 1966. The members were riding a whirlwind in the spring of 1966, which showed -- along with a lot more -- in this album's unintentionally revealing cover photo, depicting all four of them framed in a window, the other three standing while Michelle Phillips reclined in front, bisecting the trio behind her. She looks happy, even pleased with herself, while the others look just a little tired, even fatigued -- a lot like the Beatles did on the cover of Beatles for Sale, the main difference being that the latter album was made two years into their international success, while this album was just a few months into the Mamas & the Papas' history as a recording act.

If the demands and rewards of success -- the concerts, the money, the drugs, and the need to keep up the quality -- were causing the group to burn the candle at both ends, Michelle Phillips' extra-curricular romantic activities with Denny Doherty burned it right through the middle, and did a lot more than bisect the group -- it disrupted all of the interlocking relationships, including her marriage to John Phillips and any trust that she shared with Cass Elliot (who had long adored Doherty), as well as greatly complicating Doherty's relationships with all of them; and another problem was her relationship with Gene Clark, formerly the best singer and songwriter in the Byrds, with whom she was flirting very publicly and spending lots of time with in private during that season. Phillips was finally dropped from the group in late June and replaced by Jill Gibson, a friend of the band, a girlfriend of producer Lou Adler, and a good singer who did a few shows with them before it was decided that they needed Phillips back -- at one point, a cover photo with Gibson replacing her in the window was prepared, but it was never used, though billboards of that shot were put up to promote the upcoming release. Gibson did end up on parts of the album, but precisely where is one of the great unanswered questions to this day.

As to the album, it still holds up magnificently as music, and shows how, even juggling live performances, television appearances, a marriage going bad, and Lord knows what drugs in his life, John Phillips could think on his feet and create like few people this side of John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Martin, and get the others to work it his way -- "No Salt on Her Tail" started life as a backing track to a Rodgers & Hart song on a television special that Phillips thought was too good not to use on one of his own songs, and he wrote one just for that track that was more than good enough to open the album. Indeed, the song has an almost tragic beauty about it -- one gets a strong sense of sadness behind the words and the music and between the lead vocals and the soaring harmonies, while uncredited guest organist Ray Manzarek of the not yet famous or especially successful Doors plays an Al Kooper-ish, "Like a Rolling Stone"-style keyboard; Hal Blaine's drums and Joe Osborn's bass provide a rock-solid rhythm section; and Eric Hord, Tommy Tedesco, and John Phillips' guitars chime away. All of it sounds a little like the Byrds channeled through God. "Trip, Stumble and Fall" was lyrically more ambitious than anything on the first album, and offered luscious harmonies, while "Dancing Bear" was an art song, opening with a small orchestral accompaniment in the foreground that recedes, switching to an acoustic guitar accompaniment and voices almost totally isolated, a cappella style, building layer upon layer in their accompaniment as though the quartet was suddenly transformed into the Serendipity Singers. "Words of Love" was Cass Elliot's great showcase, giving her the spotlight that she filled magnificently with an elegant, bluesy pop sound -- and then comes Rodgers & Hart's "My Heart Stood Still," which is transformed into a 12-string-driven, horn-ornamented piece of folk-rock, and it leads into the first side's finish, "Dancing in the Street," arguably the best straight blue-eyed soul rendition ever done of a Motown number and also the song that resulted from Michelle Phillips' return to the fold in the summer of 1966.

Side two opened with John Phillips' masterpiece, "I Saw Her Again," the hardest-rocking song of the group's history as well as the place where he crossed swords with the Beatles as a songwriter and producer, and succeeded in matching them. "Strange Young Girls" was a hauntingly beautiful yet ominous take on the youth scene in Los Angeles at the time, and then there was "I Can't Wait," an angry but beautifully harmonized bitter love song, with a bassline that's one of the most memorable instrumental moments in the group's history, all about a busted romance. The latter song, the equally venomous "That Kind of Girl," the bittersweet "Even if I Could," plus the singles "Words of Love" and "I Saw Her Again" all seemed to reveal more about what was happening to the band than any press release could have -- some of what's here is mean-spirited enough that garage punk misogynists the Chocolate Watch Band could have covered it without too much trouble. They combine to make this album one of the nastiest-tempered statements of romance in a mainstream rock album of its era, and a lot edgier than any other long-player the group ever issued. (And for those who want to hear an almost equally good folk-rock album that is a companion piece to this album, check out Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers, recorded a little later than this album -- listen to some of the more cynical love songs and one must wonder seriously if Clark wasn't, consciously or not, giving his "take" on the relationship with Phillips.) The Mamas & the Papas does end on a harmonious note, however, with the equally bittersweet "Once Was a Time I Thought," a piece of vocalese that rivals the work of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross and anticipates the records of the Manhattan Transfer, and might be the group's single best vocal performance. It's all a good deal messier than the first album, but it holds up just as well and is just as essential listening.