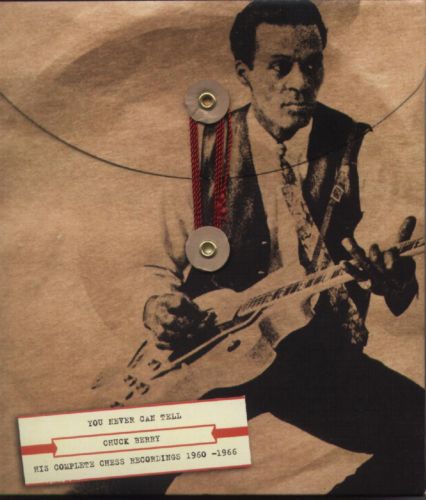

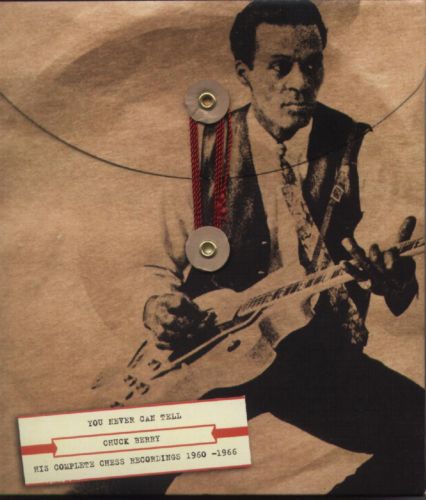

On the 1961 single "Go Go Go," a side that went nowhere on the charts, Chuck Berry sang that he was "Mixing Ahmad Jamal in my 'Johnny B. Goode'/Sneaking Erroll Garner in my 'Sweet Sixteen'/Now they tell me Stan Kenton is cutting 'Maybellene'" -- as always, Chuck is stretching the truth to fit his story. Kenton never cut "Maybellene" but Berry did sneak some jazz into his rock & roll in the '60s, along with plenty of blues, country, and some folk, all evident on You Never Can Tell: The Complete Chess Recordings 1960-1966, Hip-O Select's second volume of Chuck's Chess recordings. Of course, Berry never was stylistically pure -- he invented rock & roll by marrying hillbilly and the blues -- but on his '60s sides he had the opportunity to both stretch out and dig deep, sometimes cutting a set of blues, sometimes expanding with horns or backing vocals or cutting a Twist. The latter is pretty good evidence that some of these wanderings may have been reflections of the times, but as a whole body of work the four-disc You Never Can Tell -- which gathers all the master studio takes, adds some alternates to the mix, and unveils a previously unheard live date that presents the rarest of things: a full adult-oriented concert given by Chuck at a Detroit casino where he was backed by an uncredited group of Berry Gordy's all-stars -- feels like the work of a man who is fully aware of his strengths and abilities, able to subtly tweak them toward the times without losing his identity.

Indeed, one of the striking things about the set is how vigorous Chuck Berry seems in the first half of the '60s, a time that did not treat all '50s rock & rollers particularly well. Of course, Chuck was not immune to the downward dip in rock & roll in the early '60s: he was arrested for a Mann Act violation in 1959 and spent the first years of the '60s embroiled in a legal mess leading to a five-year jail sentence of which he served roughly a year and a half. Before he entered prison, he recorded furiously: about the first disc and a half of You Never Can Tell dates from 1960 and 1961, as Chuck was laying down as many sides as he could, just in case he went away for a long time. Some of these sessions do seem a little hurried -- there aren't many originals, particularly in 1960 -- but this did give him an opportunity to record some very good blues-heavy sessions, where he was able to indulge in his fondness for Charles Brown, Nat King Cole, and Amos Milburn. And while there weren't many originals, those that were there were quite good, especially the "Johnny B. Goode" sequel "Bye Bye Johnny" and his latest car song, "Jaguar and Thunderbird." The 1961 sessions produced an even stronger crop of originals with "I'm Talking About You," "Come On," "Go Go Go," the "Junco Partner" adaptation "The Man and the Donkey," and "Trick or Treat," the latter two appearing on the excellent fake live album Chuck Berry on Stage (the cuts here being presented without the audience overdubs).

Chess planned to launch Chuck's post-prison comeback with a genuine live album recorded at Walled Lake Casino in Detroit in October of 1963, but the record was scrapped, laying in the vaults unreleased until this set. The very reasons why the album was abandoned are why it's such thrilling listening now: the performances are rough and ragged, with Chuck lurching from mood to mood on the closing medley of "Goodnight Sweetheart Goodnight," "Johnny B. Goode," "Let It Rock," and "School Day," and he spends an inordinate amount of time telling corny old jokes from the stage. It's hardly perfect, but it's a rare glimpse into Berry's on-stage charms and a vital live document of early rock & roll that's more interesting now than it might have been at the time. In any case, Chuck didn't need the boost from the live set: he came back stronger than ever in 1964 with the hits "Promised Land," "No Particular Place to Go," "You Never Can Tell," and "Nadine," all featured on his classic LP St. Louis to Liverpool, its title an explicit reference to how his music inspired the British Invasion.

Discounting Elvis, who existed in his own category by that point, and the Everly Brothers, who continued to have hits, Chuck Berry was the only rock & roller who rubbed shoulders with his progeny, due both to his clear influence on the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and also his vigorous writing. Berry's mid-'60s work rivals his late-'50s work, perhaps not in terms of innovation but in sheer lyrical and musical might; this is plainly apparent in the aforementioned quartet of hits, each one as crisp and clever as "Brown Eyed Handsome Man" and "Johnny B. Goode," but he had plenty of unheralded gems during this stretch, including the dynamite "Dear Dad" (a song so compact and blazing that plenty of punks cut it about a decade later), "It Wasn't Me" (a song he revisited in the '70s), "My Mustang Ford," "It's My Own Business," and "Ramona Say Yes." Add to that Chuck's instrumental jam LP with Bo Diddley -- an album consisting of two tracks that ran well over ten minutes, a length nearly unheard of on a rock & roll record in 1964 -- and some additional blues, and Berry's '60s sessions amount to a truly remarkable run that deepens and adds new dimensions to what was already one of the greatest legacies of 20th century American music.