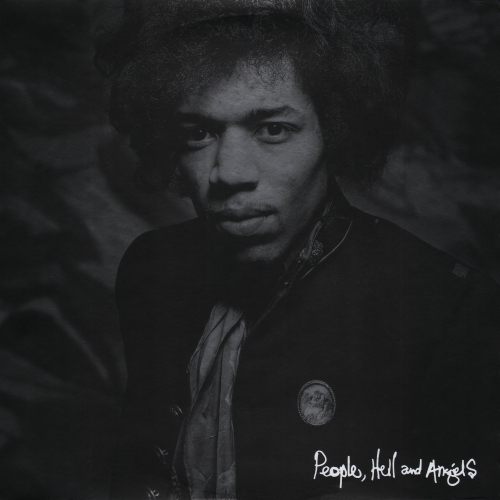

People, Hell and Angels

Studio album by Jimi Hendrix

Released March 5, 2013

Recorded March 1968 - August 1970

Genre Rock

Length 51:53

Label Legacy

Producers Jimi Hendrix, Eddie Kramer, Janie Hendrix, John McDermott

People, Hell and Angels is a posthumous studio album by the American rock musician Jimi Hendrix. The fourth release under the Experience Hendrix deal with Legacy Recordings, it contains twelve previously unreleased recordings of tracks he was working on for the planned follow-up to Electric Ladyland.

The tracks featured on People, Hell and Angels are previously unreleased recordings of songs that Jimi Hendrix and fellow band members (mainly the Band of Gypsys lineup featuring Billy Cox and Buddy Miles) were working on as the follow-up to Electric Ladyland, tentatively titled First Rays of the New Rising Sun. The majority of the recordings are drawn from sessions in 1968 and '69 at the Record Plant Studios in New York, with a few inclusions from Hendrix's brief residencies at Sound Centre, the Hit Factory, and his own Electric Lady Studios.

According to Eddie Kramer, the engineer who recorded most of Hendrix's music during his lifetime, this will be the last Hendrix album to feature unreleased studio material. Kramer said that several as-yet-unreleased live recordings would be available in the coming years.

Professional Ratings:

allmusic 3.5/5 stars

The Guardian 4/5 stars

NME 8/10 stars

Rolling Stone 4/5 stars

Slant Magazine 4.5/5 stars

Review by Sean Westergaard of allmusic:

People, Hell and Angels is a collection of quality studio tracks recorded (mostly) in 1968-1969 as the Experience was coming to an end and Jimi was renewing his friendships with Billy Cox and Buddy Miles, who appear here as sidemen on most of these tracks. The surprising thing about this set is not the sound quality (which is exceptional) or that these all sound like finished tracks, but the fact that even avid Hendrix bootleg collectors are unlikely to have heard most of this material.

A great version of "Earth Blues" kicks things off with just Jimi, Billy, and Buddy (whose drums were replaced by Mitch Mitchell on the Rainbow Bridge/First Rays version). It's a more forceful take than the other version and also has some different lyrics. "Somewhere" is also a different take than the one used for Crash Landing and, of course, contains the original rhythm section and not the egregious overdubs of Crash Landing. "Hear My Train A Comin'" and "Bleeding Heart" are both taken from Jimi's first session with Billy and Buddy from May of 1969. In the film Jimi Hendrix, "Hear My Train" is played slow on a 12-string acoustic and sung so sadly that you can actually see a tear on Jimi's face as he sings. This version is not only electric and taken at a faster pace than normal, but it's an angry song, this time with a killer solo. "Bleeding Heart" is nice and raw and has a VERY different arrangement than he ever performed live. "Let Me Move You" was recorded with saxman Lonnie Youngblood, who released a couple singles with a pre-Experience Jimi Hendrix on guitar. It's nothing more than an old-school soul jam except the guitar is way more out front. It's a decent track, but doesn't really fit in with the sound of the rest of the album. "Izabella" and "Easy Blues" are rare studio recordings by the Woodstock band (Jimi, Billy, and Mitch Mitchell with Larry Lee on second guitar and Jerry Velez and Juma Sultan on percussion). This version of "Izabella" is now the earliest known recording of the song, while "Easy Blues" is actually a nice jazzy instrumental (previously released in edited form on Nine to the Universe).

This version of "Crash Landing" has Jimi and Billy with what is essentially a pickup band. It sounds more like a work in progress than anything else on the set and contains many elements of what would become "Dolly Dagger." "Inside Out" may have been heard by hardcore collectors, but not in this quality. It was originally cut with just Jimi on guitar and Mitch Mitchell on drums, then Jimi added bass and a guitar overdub through a Leslie. It's a great tune and it's always exciting to hear Jimi's bass playing as well. "Hey Gypsy Boy" is very closely related to "Hey Baby," and may have been an early version. On this cut, Jimi's whammy bar work is quite interesting and not his standard dive-bomb approach. "Mojo Man" was actually a Ghetto Fighters tune, recorded at Muscle Shoals. Jimi laid down a couple guitar tracks on top of the existing mix for this track. Kudos to Eddie Kramer for grafting guitar parts on to a fully mixed tune and making it sound great (he really did a spectacular job on this entire set). It's a hot tune with nice syncopated horns, improved by Jimi's addition. The album closes with a brief studio take on "Villanova Junction Blues."

People, Hell and Angels certainly isn't the place to start your Hendrix collection, but collectors will surely want to hear this and it provides an interesting perspective on where Jimi's music was headed post-Experience.

Review by Patrick Humphries at BBC Music:

The battle for the soul and spirit of Jimi Hendrix continues undiminished. The problem with Jimi is that he never stopped making music – he left behind an estimated 1,500 hours of material when he died in September 1970. The irony is, of course, that Hendrix died so young – he didn't even make it to 30 – that his legacy was built upon just four albums that he released in his lifetime. This is the 12th official studio set released since Hendrix’s death. The last, 2010’s Valleys of Neptune, proved his appeal hadn’t waned: it charted top 30 in the UK, and reached No. 4 on the Billboard 200 stateside. The very nature of Hendrix's approach to recording was due in large part to the fact that, having his own studio, he was not at the mercy of a record label. This freedom produced his amazing archive. Inevitably, much of the material that has subsequently surfaced is made up of studio jams – but when you are dealing with a guitarist of such stature, even jams can be a revelation. Hendrix's music was rooted in the blues, as demonstrated here by Hear My Train a Coming' and Bleeding Heart. On Somewhere, a previously unreleased cut from 1968 with long-time Jimi fan Stephen Stills on bass, the sheer fluency of Hendrix's playing is breathtaking. A jam with saxophonist Lonnie Youngblood is also enjoyable, and equally welcome is the inclusion of original versions of songs that are more familiar in posthumous versions with overdubs and editing. While the debate still rages about where his muse might have taken him next, few would question Hendrix's place in the pantheon of rock greats – after all, Miles Davis didn't offer to play with just anyone. No one knows for certain, but this latest collection offers a tantalising glimpse of how Hendrix's genius might have progressed.

Review by Jon Hadusek on Consequence of Sound:

When Jimi Hendrix died, he became a god. This is an undisputed fact. It’s all been said before, regurgitated by rock writers for decades: Hendrix revolutionized the art of guitar playing. He viewed the instrument as a sonic anomaly, his playing an ongoing experiment conducted during every jam session and live show. Scales, chords, progressions — all that stuff had already been discovered. Hendrix was fascinated by what hadn’t been done with a guitar– like playing it through wah-wah pedals and massive gain, or picking its strings with his teeth, or dousing it with lighter fluid and igniting it. His godliness is directly correlated to his larger-than-life fretwork.

So when he died, he ascended to the rock ‘n’ roll heavens, where his divine amplifier feedback can be heard for all of eternity. Us mortals were left with loose ends: demos, outtakes, unfinished recordings, archived live audio, and stray handwritten lyrics. They were scraps to some, $$$ to all the music industry execs who knew how to exploit the death of an icon.

The first three posthumous LPs — The Cry of Love, Rainbow Bridge, and War Heroes — were produced and compiled by Mitch Mitchell, Eddie Kramer, and John Jansen with the earnest intent of finishing what Hendrix couldn’t (most of these songs would be collected on 1997’s First Rays of the New Rising Sun in an attempt to recreate the album Hendrix was working on before he died). Admirable enough. But with the vaults open and labels placing bids on Hendrix’s unreleased material, the money grubbing ensued. The villain: record producer Alan Douglas. Starting with 1975’s Crash Landing, Douglas produced numerous albums by taking Hendrix’s leftovers and replacing the original rhythm tracks with overdubs by session musicians. After mastering, the recordings sounded more polished and professional, but less authentic. This pissed off a lot of Hendrix fans. Douglas compiled every posthumous studio album until the Hendrix estate (which operates under the name ‘Experience Hendrix L.L.C.’) gained ownership of the recordings in 1995.

Not that that’s seen a decrease in releases. Legacy Recordings and Experience Hendrix have already collaborated for some box sets and LPs, People, Hell and Angels being the latest. However, the presentation of the music differs. This partnership has taken an archivist approach to preserving and releasing posthumous material — the opposite of what Douglas did. No overdubs. You’re hearing Billy Cox on bass and Buddy Miles on drums (the Band of Gypsys!). Stephen Stills shows up. The recordings sound raw– and real.

Opener “Earth Blues” is a tight rock-and-soul fusion and easily the catchiest tune on People, Hell and Angels. Hendrix sings his conversational jive-talk as Miles and Cox follow with a harmonized chorus reminiscent of vintage Motown. Originally featured on 1971’s Rainbow Bridge, the song is presented here in a looser form. The same goes for “Somewhere”, which sees Stills on bass. The takes are obviously candid, as if somebody just hit the record button while Hendrix and his band jammed in the studio (which is probably what happened). And the guitar solos… they’re on every song, multiple minutes in length. It’s to be expected, but it gets tiresome with repeated plays. Better are the solos that sound written rather than improvised. “Sometimes” touts one of the former, a silky romance of a solo that segues into Hendrix all down n’ out: “Back at the saloon, tears mix with mildew in my dreams.” No surprise that the two aforementioned tracks were selected as the singles for People, Hell and Angels (and they’re bound to chart, courtesy of classic rock stations everywhere).

The rest of the album is a mixed bag of brilliance and indifference. Some songs we simply don’t need another version of in our music libraries. “Hear My Train A Comin’” and “Bleeding Heart” were presented in superior form on 1994’s Blues; “Izabella” sounds good here, but better on First Rays and Woodstock. Other songs are so rough that they were probably better off unreleased (the cloying solo in the middle of “Easy Blues” is arguably Hendrix’s worst; “Mojo Man” is a Ghetto Fighters track with guitar awkwardly overdubbed into it).

Then there’s “Crash Landing”, which is so good that it’s hard to believe it went unreleased for so long (Douglas’ version doesn’t count). Hendrix sings to then-girlfriend Devon Wilson, pleading that she kick her drug addiction: “And look at you, all lovey-dovey when you mess around with that needle / Well, I wonder, how would your loving be otherwise?” His lyrics are rarely this personal and transparent. This is the kind of stuff that makes a posthumous release worthwhile.

People, Hell and Angel isn’t perfect — or godly — but it does contain some canon tracks that every Hendrix fan should hear. And for a posthumous anthology, it’s surprisingly cohesive as a singular unit. These tracks share a consistent groove that’s never urgent or lazy, but just right. Perhaps it’s the organic, jam-session sound quality. Or the Miles-Cox rhythm section. Whatever the dynamic, the Douglas-produced albums didn’t have it. People, Hell and Angels does, and no matter how flawed it might be, you can’t dispute its authenticity.

Review by Dave Simpson on The Guardian:

With almost four times as many posthumous collections as studio albums released during his lifetime, James Marshall Hendrix really may be worth more dead than alive. Most of the dozen songs here have been released before in other forms, and 1997's First Ray of the New Rising Sun remains the definitive set of "building blocks" for what would have been Hendrix's fifth album. However, these 1968-9 recordings (mostly with Billy Cox and Buddy Miles) are free of overdubs, and the playing is incendiary. Easy Blues and Elmore James' Bleeding Heart are rawer than other versions, but most intriguing are the songs where you can hear him feeling out new directions: Earth Blues and Izabella are lithe and funky, and the outstanding, sax-blasting Let You Move You, with Lonnie Youngblood's vocals, suggests Hendrix could have made a blistering metamorphosis into turbocharged electric soul.

Review by Jim Farber of the New York Daily News:

The folks who cobbled together “People, Hell & Angels,” for the estate of the late Jimi Hendrix, have been making a lot of broad claims about their product.

It’s supposed to give us 12 “previously unreleased” studio recordings “completed” by Hendrix. It’s also meant to provide a “compelling window into his growth as a songwriter, musician and producer,” offering “tantalizing new clues” to the direction Hendrix was testing for a fourth studio album. This was to be a proposed double-set sequel to 1968’s “Electric Ladyland.”

Of course, Hendrix never recorded — let alone released — that album, so it’s hard to say just how “complete” the man himself may have considered these songs. While it’s true none of these recordings have come out before, nearly all have been issued in different versions in the 43 years since the guitar god left this earthly plane.

In that time, it seems like more “lost” Hendrix recordings have been found than we now have reality shows — some of them every bit as dubious. As a consequence, only the most extreme Hendrix-ologist could divine the precise rarity of these recordings. But even a cursory listen makes this clear: The newfangled, and boldly explorative, Hendrix alleged here, captured between 1968 and ’69, doesn’t sound all that different from the one we’ve long loved. At root, it’s still killer psychedelic rock-soul, very much of its time.

The disc does find the icon working with some different musicians, including Steven Stills (on bass!), along with a second guitarist on some tracks (he is old friend Larry Lee).

Hendrix also brings in horns and other singers for some cameos. Even if these “clues” somehow “tantalize” you, they hardly provide solid evidence of any revolutionary direction fans might have imagined for the icon.

Of course, the mold Hendrix already set had more than enough juice and innovation to thrill, and if you’re a nerd about this stuff, the incremental changes teased here will excite.

It’s fun to hear the guitar immortal working with horns. In “Let Me Move You,” he features saxist Lonnie Youngblood for a blisteringly fast rock-soul workout, much in the manic mode of Ike and Tina Turner. “Mojo Man” sees Hendrix helping out old Harlem friends, the Ghetto Fighters, who sing lead, while horns pump and a rolling piano brings in a touch of New Orleans.

The funky take on “Crash Landing” rescues it from a 1975 version that caused a scandal by employing posthumously tacked-on studio musicians. But the most worthy cut is “Easy Blues,” an instrumental that’s twice as long as a take that appeared on a now-out-of-print album from 1981. As guitarist Lee plays foil, Hendrix peels out leads that fly so high, they’ll leave every guitarist who came in his wake reeling in wonder.

Review by Andy Welch on NME:

Given he died 43 years ago at the age of 27, a ‘new’ album from Jimi Hendrix might, at first glance, seem an impossible dream. But that’s not quite the full picture, as ‘People, Hell & Angels’ is no lost gem. Each of these 12 songs will already be known to fans, even though they’re all previously unheard versions from sessions that took place between early 1968 and late 1969.

Had everything gone smoothly, what’s here might have ended up on the follow-up to ‘Electric Ladyland’, tentatively titled ‘First Rays Of The New Rising Sun’. It never happened, of course, but this collection has a tantalising flavour, the sense of an alternative history of rock. Various musicians drop in and out of the electric blues workouts, including Jimi Hendrix Experience bandmate Mitch Mitchell, old army buddy Billy Cox, drummer Buddy Miles, saxophonist Lonnie Youngblood, and Stephen Stills, who plays bass on ‘Somewhere’. This is the track, full of Jimi’s explosive wah-wah guitar, that first puts ‘People, Hell & Angels’ in a different league to many of the other Hendrix cash-ins filling up the bargain bins.

There are notes of will-this-do here, too – neither ‘Easy Blues’ or ‘Hey Gypsy Boy’, with their jazz-lite noodling, will be hailed as the Hendrix Holy Grail. But there are special moments: the laid-back ‘Hear My Train A Comin’’, remastered by Jimi’s friend and engineer Eddie Kramer, has a Technicolor vibrancy that belies its age; a cover of slide guitar player Elmore James’ ‘Bleeding Heart’ is vital, and so old-school it sounds black and white. Initially recorded by The Ghetto Fighters at the legendary Fame Studios, this was an unremarkable soul stomper before Hendrix overdubbed his unmistakable playing.

There’s no shortage of posthumous Hendrix. He only released four long-players before his death in 1970; three times as many have been released since, and that’s before you get into unofficial bootlegs. If you’re going to get one of them, make it this.

Review by David Fricke of Rolling Stone:

Jimi Hendrix made three historic studio albums in 1967 and '68. He spent the rest of his life laboring and failing to finish a fourth. But it was a rich if chaotic time, and we're not done with it. These studio jams and early stabs at evolving songs mostly come from 1969 as Hendrix worked with shifting lineups, indecisive about his post-Experience path. Three tracks date from a May session, his first with Billy Cox and Buddy Miles, the future Band of Gypsys, including a funky turn through the signature blues "Hear My Train A Comin'." A rough "Izabella" with his short-lived Woodstock band comes with a diving-jet solo. Of course, Hendrix plays at an elevated level in every setting: a workout with saxman Lonnie Youngblood; the overdubbed-guitar chorales in the '68 instrumental "Inside Out." Hendrix left us so much but in precious little time. Every shred counts.

Review by Ted Scheinman on Slant:

People, Hell and Angels isn't a jumble of Jimi Hendrix B-sides, nor does it feature half-formed songs given the ProTools treatment. And there isn't a single "live" track to be found on the album. (Robert Christgau wrote in 1986 that "after years of repackaging, only suckers and acolytes get hot for another live Hendrix album." Christgau was not an acolyte.) In fact, People, Hell and Angels delivers crisper delights than 2010's Valleys of Neptune, interpolating less obvious (and far less accessible) material while also standing as a well-crafted, deftly paced album in its own right. The longest song runs less than seven minutes—a quantifiable indication of the album's unthreatening nature, and a testament to the good sense of Eddie Kramer (Hendrix's George Martin and the engineering sage behind the new album).

Recorded, sometimes in secret, between March, 1968 and December, 1969, People, Hell and Angels comprises 12 tracks that pop with an electricity born of Hendrix's sense of forward motion—in his capital-A art, but also in his own playing and ability to galvanize a rotating band of non-Experience types, including Stephen Stills, Lonnie Youngblood, Rocky Isaac, plus perennial accomplices Mitch Mitchell, Billy Cox, and Buddy Miles. In other words: 19 Great Performances this ain't, and thank God. Instead, we get airtight playing and new, consistently interesting material—plus more than a glimpse of the musical space toward which Jimi was feeling his way. This is Hendrix shifting into funk, but also minimalism-as-maximalism via virility and volume—that is, in the vein of Sabbath and Zeppelin (two bands forever indebted to Hendrix), People, Hell and Angels contains a quartet of songs each built on a single one- or two-string monster riff. Chord changes matter about as much here as they do on Bitches Brew. Nineteen sixty-eight to '69 was Hendrix's finest period on stage, his eyes closed even as he did the work of two guitarists without ever appearing to exert himself. On the genre experiments that appear here, Hendrix's guitar does the head, the A section, and the B section. One riff gives way to another, so that even Hendrix's more excursive sallies are by their very nature overloaded with hooks.

That's a beautiful thing, but there's something even more beautiful in hearing Jimi as accompanist, amid well-charted horns and hard-Doppling Leslie organs. On Valleys of Neptune, Kramer overdubbed backing tracks that Mitch Mitchell, Noel Redding, and Cox recorded in the late '80s. Here, there's no need; all the musicians are in place, even if some of them remain anonymous—a pitfall of recording "unofficially" all over the U.S. and the U.K. Each track rings true to its time, but Kramer's sequencing and editing elevate these individual "finds" into a disc that merits the full-listen treatment. The jazzy extract of "Easy Blues" that feels so natural on the second half of the album was cut from a take of ungodly length, but Kramer shapes everything so well that the excisions never show and the inclusions never bore.

Melodic guitar breaks on "Somewhere" recall the non-blues elements of Axis: Bold As Love; "Hear My Train A-Comin,'" Hendrix's first time recording with Cox and Miles, is pentatonic beer-rock (though this version is no mere artifact—it crackles harder than the version on Valleys of Neptune); and Hendrix reverts to his usual psychedelic blues at various other moments. But the importance of People, Hell and Angels is that it takes Hendrix's whole late-era gypsies-rainbows-and-sun sensibility and strips the excessive to the elemental. Despite rumors of imminent collaborations with Emerson, Lake & Palmer (or John Lennon, or Miles Davis, or a hundred other putative artists), Hendrix was most likely headed (in a slightly less earthbound sense) toward the Sly Stone model. His promiscuous late-career collaborations and increasing eagerness to work with horns certainly suggests this, as does Hendrix's willingness to get ushered toward funk by Buddy Miles. ("Crash Landing" is some of the funkiest guitar Hendrix has played, even considering the 1970 Fillmore New Year's material and the Woodstock album itself.) Elmore James's "Bleeding Heart," as delivered on People, Hell and Angels, is a different song entirely from the one Hendrix had played with the Experience at Royal Albert Hall in 1969; on this track, one can hear Cox and Miles actively pushing him ever closer to funk. "Mojo Man," which features the Ghetto Fighters, is Muddy Waters via Funkadelic, with Hendrix doing workmanlike accompaniment and a vicious call-and-response with the bari sax.

Hendrix would tiptoe around the whole funk idiom until his untimely death. But no one—not even Hendrix—knew exactly where he was going. The fan's riddle is that there's always so much suspicious "new" material that it's hard to know the wheat from the chaff. This posthumous glut is a result of Hendrix's enviable artistic freedom: He owned his masters and owed no single studio his loyalty. That freedom can birth some surprising gems, too, and People, Hell and Angels is one of them. Searching for a meaningful fusion of the crazy sounds bouncing through his head, Hendrix decided to collaborate more expansively, and the first fruits of this inclusive sensibility are promising. The album, then, is both delightful and very sad indeed. "I see fingers, hands, and shades of faces/Reachin' up and not quite, uh, touchin' the promised land," Hendrix sings on "Somewhere." What distinguishes him from a subsequent parade of presumptive heirs is this sense of reach, whether it be musical or spiritual. Put bluntly, the dude had "soul," a word whose connotations broadened in very interesting ways through the '70s. People, Hell and Angels offers the clearest sense yet of how Hendrix was preparing an evolution of his own.

LP track listing

All songs written by Jimi Hendrix except as noted.

Side One

1. "Earth Blues" - 3:33

2. "Somewhere" - 4:05

3. "Hear My Train A Comin'" - 5:41

Side Two

4. "Bleeding Heart" (Elmore James) - 3:58

5. "Let Me Move You" - 6:50

6. "Izabella" - 3:42

Side Three

7. "Easy Blues" - 5:57

8. "Crash Landing" - 4:14

9. "Inside Out" - 5:03

Side Four

10. "Hey Gypsy Boy" - 3:39

11. "Mojo Man" (Taharqa Aleem, Tunde-Ra Aleem) - 4:07

12. "Villanova Junction Blues" - 1:44

Recording Details:

* Track 1 recorded on December 19, 1969 at Record Plant Studios

* Track 2 recorded on March 13, 1968 at the Sound Centre

* Tracks 3, 4 and 12 recorded on May 21, 1969 at Record Plant Studios

* Tracks 5 and 10 recorded on March 18, 1969 at Record Plant Studios

* Tracks 6 and 7 recorded on August 28, 1969 at the Hit Factory

* Track 8 recorded on April 24, 1969 at Record Plant Studios

* Track 9 recorded on June 11, 1968 at Record Plant Studios

* Track 11 recorded in June 1969 at Fame Studios, Muscle Shoals, Alabama; overdubs in August 1970 at Electric Lady Studios

* Track 13 recorded on January 23, 1970 at Record Plant Studios

Personnel:

* Jimi Hendrix – guitars, vocals, bass guitar (track 9)

* Billy Cox – bass guitar (tracks 1, 3, 4, 6–8, 13)

* Buddy Miles – drums (tracks 1–5, 10, 13)

* Mitch Mitchell – drums (tracks 6, 7, 9, 12)

* Juma Sultan – congas (tracks 3, 4, 6, 7, 12)

* Larry Lee – rhythm guitar (tracks 6, 7)

* Jerry Velez – congas (tracks 6, 7)

* Stephen Stills – bass guitar (track 2)

* Lonnie Youngblood – vocal & saxophone (track 5)

* Rocky Isaac – drums (track 8)

* Al Marks – percussion (track 8)

* Albert Allen – vocal (track 11)

* James Booker – piano (track 11)

* Gerry Sack - triangle & mime vocal (track 6)