Jun 1, 1891-Jan 1922

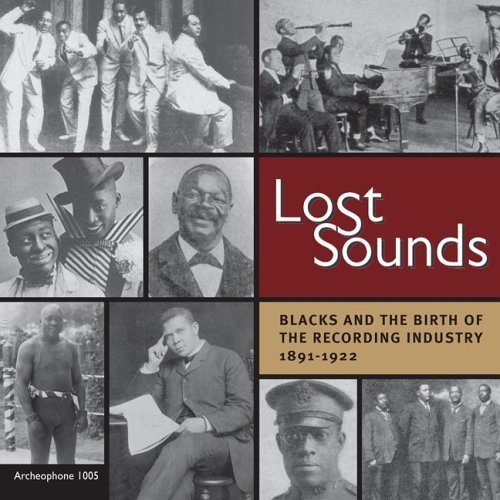

Archeophone's two-disc set Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry 1891-1922 has its genesis in a book by author Tim Brooks. Conventional wisdom used to dictate that African-American artists just simply didn't make records until the advent of Mamie Smith's 1920 "Crazy Blues," a view one still may encounter in half-researched puff pieces and on less-informed websites. Brooks' weighty tome takes the date back to 1891, when the commercial recording industry itself was only one year old, and uncovers the existence of more than 800 recordings featuring the talents of African-American performers made before Mamie Smith's debut turn. Not all of these records are necessarily easy ones to love by current day standards; many are minstrel songs and comedy records of the kind those of a politically correct bent would love to see disappear into the mists of history forever. Archeophone, however, has thankfully decided to throw caution to the wind, and to let the truth be known. Lost Sounds reflects a cross section of the material that Brooks covers in his book. Here one can find opera singers, vaudeville stars, early jazz and ragtime bands, and gospel vocal groups in addition to the expected "darkey" sketches and plantation songs. Lost Sounds takes listeners further back with the black experience than any collection, on CD or LP, that has preceded it.

Some may take exception to the ancient audio quality of these 100-year-old recordings, though others more used to the sound of audio as captured in these technically primitive formats will be surprised at how outstandingly well some of these selections come across. "Brother Michael Won't You Hand Down That Rope," as sung by the Oriole Quartette from the impossibly distant era of 1895, reproduces with astonishing clarity for a brown wax cylinder, and many of the other, more recent selections taken from discs are heard as clear as day. In the minority are some tracks that are both ultra-rare and significant, but only dimly audible, such as the cylinder of 1895 by minstrel comic Louis Vasnier. Made by the Louisiana Phonograph Company, it may be as close as listeners ever come to hearing the lost Buddy Bolden cylinder, the only record made by the artist credited as the father of New Orleans jazz. Even more startling are two 1898 recordings made by minstrel singers Cousins & DeMoss that bear an uncanny resemblance to the country string band music of the century to come.

Recording pioneer George W. Johnson, believed to be the earliest African-American to make records, is heard in several selections, as is a speech given by Booker T. Washington in 1908. The more formal side of black American music-making is experienced in the early singing of operatic baritone Roland Hayes and in pieces composed and performed by classical composers R. Nathaniel Dett and Harry T. Burleigh. The set closes with some of the earliest examples of black jazz artists, including Eubie Blake, Wilbur Sweatman, and W.C. Handy. This brief description barely scratches the surface of the 54 treasures included within this excellent set.

A generous and well-researched booklet within Lost Sounds includes discographical details and many photographs; the booklet itself is almost worth the cost of the set. Taken together, all of the elements making up Lost Sounds serve to elaborate history, not as some pompous historian with an agenda might have, or want it, but as the phonograph left it to listeners. For those with a genuine interest in the history of African America, its music, and its culture, Lost Sounds will be like the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls were to scholars of Judaic history. No American library should be without it, and Lost Sounds would make a wonderful gift for a relative or friend who is enthusiastic, or even merely curious, about African-American music before the dawn of jazz.