Dr. John has been described as ‘’the living embodiment of New Orleans culture’’. His gravely voice and crazy fusion of New Orleans R&B, rock and Mardi Gras have created a unique ‘Voodoo’ sound, aptly demonstrated on these thrilling 1991 sessions with the Donald Harrison Band.

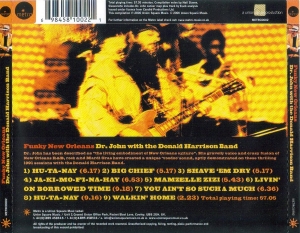

Track List 1 Hu-Ta–Nay

2 Big Chief

3 Shave ‘Em Dry

4 Ja-Ki-Mo Fi-Na-Hay

5 Mamzelle Zizi

6 Livin’ On Borrowed Time

7 You Ain’t So Such A Much

8 Hu-Ta-Nay

9 Walkin’ Home

The Biography

'I hope I'm not schizophrenic - but I could be,' Dr. John (alias Malcolm John Michael Crow Rebennack) said in a recent interview. Let's face it, he ought to have his alter ego under control by now. As Barry Humphreys totally inhabits Dame Edna when the slap goes on, so Mac becomes the benevolently menacing Dr. John when he shambles onstage. He's been described as 'the living embodiment of New Orleans culture', a compliment he's loath to acknowledge.

'That's one good thing 'bout being from this city,' he replied when Paul Trynka asked if such notice imposed responsibility. 'People ain't all that responsible.' There's humour and truth in that riposte. If push came to shove, he'd probably prefer to be the embodiment of all the things New Orleanians prefer not to admit, the forms of speech, the convoluted musical traditions, the hoodoo hex hovering over the inhabitants, tempting disclosure but avoiding definition. 'I always think there's two or three forms of New Orleans music that don't get recorded,' he's said and then, 'there's a lot of them that get recorded too much.'

His role is one he didn't envisage when he first started hanging round the clubs and studios where the classic brand of New Orleans R&B, which he now refers to as 'da fonk', was formed. But during the course of his relentless pursuit of the music and its practitioners, he absorbed the essence of its unique traditions and when the time came, his shoulders proved broad enough to assume the mantle his contemporaries conferred.

Music was unavoidable in the Rebennack family. 'When I was a kid growing up almost everybody in our neighbourhood had a piano. Didn't matter how poor they were, how wealthy, it was a piano that got people together. My aunt Dottie Mae who lived about three blocks from me used to have jam sessions at her pad. I think that was something in New Orleans that people used as a way to get together. They have any excuse to party, anyway. But the piano was the main thing that started the party.'

There was a piano at home, too, for his sister and later Mac to practise upon. She was ten when Malcom arrived on November 21, 1940. 'I was hypnotised by its beautiful white sheen and the way it glowed like a ghost in the evening light,' he wrote in 'Under A Hoodoo Moon', his quirky autobiography. His father had an appliance store that also sold records. 'My father used to fix radios and PAs. He was very much into electronical stuff, phonographs and all of that, and I was lucky enough to go around with him to clubs when he'd be fixing the PA.'

Ah yes, the clubs, they were unavoidable, too. 'There was a place called the Texas Lounge, on Canal Street, where I used to walk to school. Annie Laurie used to sing there with Paul Gayten's band and I had this childhood crush on her. So I just used to stand outside, looking and kinda admiring her. And that's where I met Red Tyler the first time and Roy Montrell, one of my guitar teachers.' The others were Al Guma and Walter 'Papoose' Nelson, guitarist with Fats Domino and Professor Longhair.

Apparently he was an easy study for one day Nelson send the teenager to stand in for him at a Paul Gayten session. 'He knew me from being a kid that used to aggravate the hell out of him and was really mad. But - whatever - he must have liked me enough to hire me back. So it opened a big door and changed my life.' Before long he was using a small office at Cosimo Matassa's celebrated studio to write songs and audition artists. He also got to know record company men like Harold Batiste and Johnny Vincent, the man who recorded Guitar Slim's 'Things I Used To Do' and then started Ace Records.

'Then Johnny gave me $60 per week auditioning talent, getting arrangers for the songs, finding the songs for them, hiring the band and cutting the record and turning it in. I worked hard and never did get the $60.' But he did get studio time to cut his own demos and experiment with musicians. Out of that came his first single, 'Storm Warning', a New Orleans take on the Bo Diddley beat. He also produced records by Roland Stone, Chuck Carbo, Sugar Boy Crawford and Ronnie Baron, who sang in the group Mac had put together.

He'd also become friendly with piano prodigy James Booker, who taught him how to play the Hammond B3 organ. 'That was in like '62 and I started on this gig. It was a great gig to have 'cause we used to play seven nights a week, every night of the year. Might play one set with exotic dancers, another was a dance gig and the last would be like a jam session - that was the gig.'

There was always a session to lead or take part in and there were always drugs to speed him up and slow him down. He'd started on weed at the age of 12 and was a heroin addict before he was 20. There came a time in 1963 when DA Jim Garrison cracked down on the city's clubs and the corruption and drug business that surrounded them. Mac Rebennack became one of the casualties and was shipped off to Fort Worth federal prison. When he emerged two years later, he was forbidden from returning to New Orleans and boarded a plane for Los Angeles.

When he arrived he joined up with other New Orleans refugees like Earl Palmer, Jessie Hill and Alvin 'Shine' Robinson. He renewed his friendship with Harold Batiste to form Hal-Mac Productions and it was through this that Mac acquired his new identity. 'Me and Harold were doing a record (which became 'Gris-Gris') on Sonny and Cher's studio time. Sonny's manager at the time, Joe DeCarlo, helped us hook a deal up. They put the thing out and I wasn't really expecting it to be much more than a one-off deal but the record kept selling.'

In 1967 Dr. John The Night Tripper, his fantastic garb and his music's eerie call to intoxication, legal or otherwise, struck a resounding chord with the psychedelic generation. Deep into his own drug problem, Mac couldn't foresee the public's reaction. 'We thought 'Gris Gris' was just keeping a little of the New Orleans scene alive, it didn't sound that freaky to me. Man, we didn't have a clue about hippies. We thought anyone who smoked a joint in public was outta their minds!'

'Babylon', 'Remedies' and 'Sun, Moon And Herbs' followed but the approach had become somewhat formulaic by 1971. A meeting with Jerry Wexler established that both men had huge respect for Professor Longhair, one of New Orleans' most famous and individual pianists. From that the ingredients for 'Dr. John's Gumbo' were prepared, a tribute to the songs and the musicians that formed the backbone of the city's musical life. 'It turned a lot of people on to checking out the original records, where all the stuff came from. It helped a lot of people and caused a bit of commotion for Professor Longhair.'

It also set him on the course that he continues to pursue to this day, the quiet eye of a storm of righteous, rhythmic mayhem. He's no longer Mac Rebennack except to his family; to the rest of the world he's Dr. John, perfectly described by Barney Hoskins: 'It's less the hat and the braces and the famous walking-stick you fix on, more the sheer size of the man's huge moon face and the history embedded in it. It's the eyes - stoical, sleepy - which have seen too much. And it's the slow, gravelly voice, thick with the music of the city whose torch he continues to carry, the Big Easy, the magical and crazy Crescent City of New Orleans.'

The Songs

Our New Orleans text comes from a 1991 recording date recorded in front of a small invited audience and shared between Dr. John and ace saxophonist Donald Harrison. Everyone loosens up with an Indian tribe chant, 'Hu-Ta-Nay', one of many to be heard on the streets of New Orleans during Mardi Gras. To the untrained ear, the words are unintelligible but the fervour and rhythmic certainty of their performance converts them to a universal musical language.

Without further ado, Dr. John kicks into a magnificent recreation of Professor Longhair's convuluted piano style on 'Big Chief', the song written by Earl King for a Longhair record date. It's an undefinable and unique admixture of Latin and Caribbean melodic strands that the Prof made his own. 'He started off as a dancer,' Mac revealed, 'which a lot of great drummers start off as, but not many piano players. But (his) piano playing was akin to drumming. It was melodic, too, but he had a real powerful vibe. When we first recorded him, we used to have to put a muffled board between his foot and the piano because he'd used the piano as a bass drum.'

The following selection is even older and is in fact the pornographic blues, 'Shave 'Em Dry', to which Mac has grafted a couple of verses from 'Mother Fuyer', the watered-down version of the Dirty Dozens previously recorded by Roosevelt Sykes and Red Nelson. Today's rap artists have brought the pejorative phrase that 'Mother Fuyer' disguises into undue prominence but even they don't usually refer to 'Shave 'Em Dry''s original premise, namely playing the two-backed beast without prior foreplay and thus lubrication. Well, you wanted to know . . .

We're back on safer ground with 'Ja-Ki-Mo', which as 'Jockomo' has a long and varied history. Virtually every New Orleans artist worth his crawfish etouffeé has recorded it and it was one of the songs on 'Dr. John's Gumbo'. As 'Iko Iko', it was a Top Twenty hit for the Dixie Cups in 1965; they tried for another hit with 'Two-Way-Poc-A-Way', promoting it in full Mardi Gras Indian mufti, but it lacked the essential simplicity of 'Iko Iko'.

Donald Harrison takes over for 'Walkin' Home', an instrumental showcase played in 5/4 time, a tempo made popular by Dave Brubeck's 'Take Five'. The tempo slows for a dowbeat beat blues, 'Living on borrowed time - but my credit's still good, I know.' It's a familiar theme given exactly the right treatment by Dr. John's cracked diction. Things get more upbeat with 'You Ain't So Such A Much', a song written and recorded in 1946 by Pleasant Joseph, otherwise known as Cousin Joe. The opening lines are justifiably famous: 'Wouldn't give a blind sow an acorn, wouldn't give a crippled crab a crutch.'

'Mamzelle Zizi' gives the band a final opportunity to flex their considerable muscles, with early notice for percussionist Howard 'Smiley' Ricks, who has worked for both Dr. John and Donald Harrison at different times. Ricks was raised on the second line rhythm that personifies New Orleans music; he calls it 'the big four'. 'When I was a little boy, you hear that big four and you run out the door. If you lived in the neighbourhood with all that going, you would catch onto it with ease. I'm a black Mardi Gras Indian chief and that's where I got a lot of my experience.'

Dr. John shares that experience and his final words hint at New Orleans' unique milieu and perhaps also his success at being his city's musical ambassador: 'Accidental stuff happens and it's better than anything you could plan.'

Neil Slaven