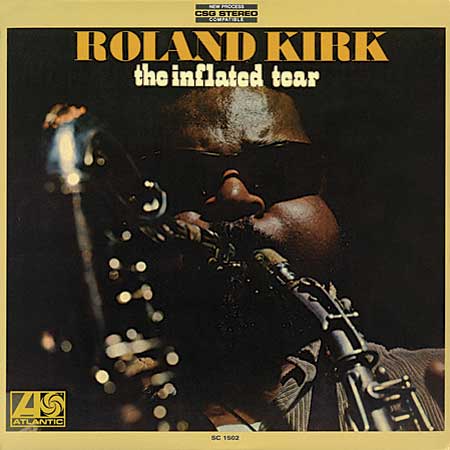

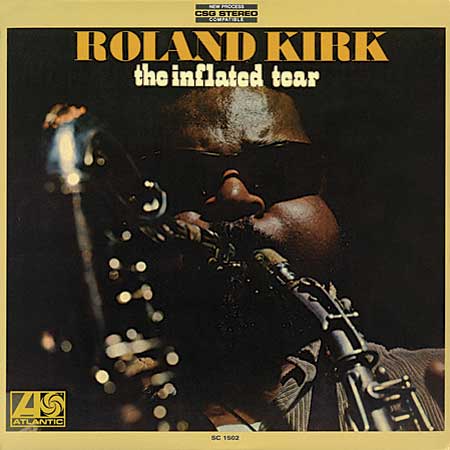

The Inflated Tear

Studio album by Roland Kirk

Released 2005 [originally released on Atlantic in 1968]

Recorded 1968

Genre Jazz

Length 38:13

Label Atlantic/Rhino

Producer Joel Dorn

The Inflated Tear is an album by Roland Kirk released in 1968. One of his most popular albums and sometimes regarded as his magnum opus, it established his reputation as a jazz composer and earned him a modicum of respect in music circles who had previously written him off as a sideshow.

Professional Ratings:

allmusic 5/5 stars

Review by Thom Jurek of allmusic:

The debut recording by Roland Kirk (this was still pre-Rahsaan) on Atlantic Records, the same label that gave us Blacknuss and Volunteered Slavery, is not the blowing fest one might expect upon hearing it for the first time. In fact, producer Joel Dorn and label boss Neshui Ertegun weren't prepared for it either. Kirk had come to Atlantic from Emarcy after recording his swan song for them, the gorgeous Now Please Don't You Cry, Beautiful Edith, in April. In November Kirk decided to take his quartet of pianist Ron Burton, bassist Steve Novosel, and drummer Jimmy Hopps and lead them through a deeply introspective, slightly melancholy program based in the blues and in the groove traditions of the mid-'60s. Kirk himself used the flutes, the strich, the Manzello, whistle, clarinet, saxophones, and more -- the very instruments that had created his individual sound, especially when some of them were played together, and the very things that jazz critics (some of whom later grew to love him) castigated him for. Well, after hearing the restrained and elegantly layered "Black and Crazy Blues," the stunning rendered "Creole Love Call," the knife-deep soul in "The Inflated Tear," and the twisting in the wind lyricism of "Fly by Night," they were convinced -- and rightfully so. Roland Kirk won over the masses with this one too, selling over 10,000 copies in the first year. This is Roland Kirk at his most poised and visionary; his reading of jazz harmony and fickle sonances are nearly without peer. And only Mingus understood Ellington in the way Kirk did. That evidence is here also. If you are looking for a place to start with Kirk, this is it.

Review on sputnik music:

Roland Kirk (later to be known as Rahsaan Roland Kirk) is one of the most interesting characters in the jazz world. Though he is most well known for his ability to play 3 instruments at once, (stritch, a straightened out Eb alto sax, manzello, a slightly curved Bb soprano sax, and the tenor saxophone), his invention of new instruments, and his charming stage persona, simply outlining his eccentricities does not do him justice. He was a very exciting improviser, and one who was capable in every area of jazz music. It may be interesting to note that he was blind for most of his life, from age 2 on up. ItÕs also pretty amazing that after a stroke in 1975 that left half of his body paralyzed, Kirk was able to continue to play the saxophone one-handed, since the technique he had employed all of his career called for it.

LetÕs break it down track by track:

The Black and Crazy Blues (6:08) - This is a great, amazingly greasy blues. ItÕs soulful and very, very laid back, with Kirk blowing incredibly tasteful on the english horn. After RolandÕs solo, Ron Burton plays a great piano solo. Near the end of BurtonÕs solo, Roland returns, now playing two horns to back him up. It feels very natural the way he slips in with the doubled harmony line. After that, itÕs back to the first melody, finishing things off. ItÕs a gorgeous tune. Some people go to church, I listen to Roland Kirk singing his soulÕs blues. 5/5

A Laugh for Rory (2:54) - This one begins with what sounds like a child talking, and then in comes KirkÕs flute, the drums, and the bass. The melody is joyful, sort of like childrenÕs song. RolandÕs solo after the melody is really cool. His flute style is pretty wild, with a lot of overtones, singing etc. Listen to Roland Kirk for a clue as to where Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull got his style. At the end of his solo, he blows his whistle, and it breaks into a swinginÕ piano solo. I love the way the piano and the rhythm section interact here. ItÕs back to the head after these two brief solos, and thatÕs that. ItÕs cute, but not the best. 3.5/5

Many Blessings (4:45) - This starts with Roland KirkÕs amazingly soulful tenor playing completely solo. Then the tune actually starts, and itÕs cool. It reminds me of something the Miles Davis 1965-1968 quintet would have played. The solo here has one over-bearing message to it: ROLAND KIRK CAN CIRCULAR BREATH. His phrases are INCREDIBLY long here, because he doesnÕt really stop to breathe at all. However, this doesnÕt come off as sounding absurd and self-indulgent, because his pacing and feel are so impeccable. ItÕs got a very defined slope, and it basically breaks off as if exhausted into the piano solo. I really like Ron BurtonÕs piano playing. He and Kirk seem to really fit each other very well, because they provide counterpoint to one another, but it always feels like a unified improvisational statement in each tune. As if Burton (who usually takes the second solo) is continuing onto whatever Roland Kirk said previously. Like before, itÕs back to the beginning melody after the piano solo, and Roland finishes things off particularly excitingly with this one. I like it a lot. 5/5

Fingers in the Wind (4:15) - Another flute tune. This one is slower than the previous two tracks, and itÕs sort of pretty. However, itÕs not my favorite. Thankfully, Roland plays a really nice solo on this one, because IÕm not all that fond of the head. Ron BurtonÕs accompaniment on this one is marvelous. His piano parts swell and fall behind RolandÕs sweeping flutter of flute notes. He doesnÕt get a solo on this one, though. Like I said, itÕs not my favorite, but I definitely like things about it. 2.5/5

The Inflated Tear (4:58) - As you might expect, the title track is one of the best on the album! This starts off with some percussion noodling. Roland plays his flexatone, and itÕs pretty cool. Then itÕs into this amazing three-horn melody/harmony part. Ahhh, I love it. Then thereÕs a little bit of flexatone again, and Roland gets on his stritch to sing us a tune. I think this may be the prettiest melody that Roland Kirk wrote for this album. Then thereÕs this dramatic fall out, and the three horn part returns. ItÕs a pleasant surprise. Back again we go to that stritch melody, followed by a similar fall out, with Roland shouting like itÕs utter chaos. More three horn stuff to finish it off. I like how this one isnÕt just head/solo/head like your average jazz tune. ItÕs got 2 distinct composed parts, and itÕs cool. 5/5

The Creole Love Call (3:54) (written by Duke Ellington) - So this is a great tune, and Kirk knows what heÕs doing with it. He plays clarinet, tenor and stritch here. Starts by introducing the melody on clarinet, then plays some of both clarinet and stritch, and takes parts of the solo on each of the three instruments. ItÕs really amazing, and an obvious stand out. 5/5

A Handful of Fives (2:42) - This tune is great, too. It starts with some drums, and in comes everyone else, Roland Kirk on manzello this time. ItÕs really hip sounding, and interesting rhythmically. ItÕs not as laid back as most of the stuff here, or as intense as ŅMany Blessings," a too-cool-for-school medium, I guess. ThereÕs no piano solo, itÕs basically just Roland Kirk showing us what he can do with a manzello. I dig. 5/5

Fly By Night (4:18) - This one starts out with some bass notes. ItÕs the first time that the bassist has really stood out to me. ThereÕs a repeated piano figure, and a cool tenor sax melody. This is another one that sort of reminds me of the Miles Davis quintet mentioned earlier. Along with Kirk is Dick Griffith on trombone, the only instance of a horn being played by anyone other than the bandleader. I like how he sounds playing harmony on the head. Kirk blows his whistle, and Griffith takes a very, very brief solo. I think itÕs only one chorus before Roland picks up with his tenor. His solo is quite short as well, giving way to a piano solo. A little bit into it, the trombone and tenor play some background stuff for Burton to solo over. Another blow of the whistle, and itÕs BASS SOLO TIME. Whoo. Steve Novosel is a good player, and although his solo is as brief as everyone elseÕs here, itÕs nice. This song has got that post-bop feel, and itÕs a cool melody with good playing. Because the solos are so short, it feels under-developed, though. 3.5/5

Lovelleveliloqui (4:04) - This melody reminds me very, very much of another jazz tune, but I canÕt recall what it is. Luckily, I like the tune it reminds me of, and I like this. Kirk is playing alto. ItÕs a lot like the other post-boppish ones. I like HoppsÕ drums on this one, it reminds me of Elvin JonesÕ playing. He finally gets to play some stretch out on this one, when he trades with Roland near the end of the tune, and then breaks into a short solo of his own. A good tune, but not one that leaves the most lasting impression. 4/5

IÕm Glad There Is You (2:12) - This is a nice little hard bop number with Roland Kirk on tenor. He plays amazingly well on this tune. He finishes the album with some sort of strange humming noises through his instrument. Hard to explain, but the tune is undeniably a gem. 5/5

Overall, this is an outstanding collection of great tunes. However, I think it lacks a feeling of unity. Like I said, itÕs a collection of songs, rather than an album.

Article by May Cobb on The Rumpus:

Songs of Our Lives: Rahsaan Roland Kirk's "The Inflated Tear"

Eighteen years ago a song unlike any music IÕd ever heard by someone IÕd never heard of before altered the course of my life. One day in a jazz history class, amid the staples of Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis, the professor slipped on a record by Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

ŅThe Inflated TearÓ sounded like the entire spectrum of the history of African-American music rolled into one four-minute song: old slavery spirituals, work songs, field hollers, soul, modern jazz, and early blues. It was like a Duke Ellington reed section, yet more emotional, more intimate, with a sound that ached of centuries. It was like listening to the inside of someoneÕs heart.

***

Best known for his ability to play three saxophones simultaneously, Rahsaan Roland Kirk lived from 1935 to 1977. Despite losing his sight as a child and suffering a paralyzing stroke, he kept playing the music that came to him, sometimes through dreams, until his death at 42.

Kirk heard music in car honks and train whistlesŠthe sounds of shattering glass, police sirens, and chirping birds were all at home in his compositions. He played everything that crossed his path, beginning with the water hose he picked up at age four, and he later commanded more than forty instruments, some of which he fabricated himself. He pushed sound and music through his battery of over-worked horns, held together by his favorite on-the-spot repair: masking tape. He was always draped in glittering instruments and wore a heavy necklace weighed down by charms and amulets heÕd received as gifts. A club owner once described him as looking like Ņa musical Christmas tree.Ó

***

A year after graduating college with an English degree, I lived in a tiny, crumbling garage apartment behind the university, and my life was now a patchwork of odd jobs and indecision. ThatÕs when I found a VHS tape of a performance Kirk gave in Switzerland during the 1970s. This was pre-YouTube, so IÕd never seen any footage of him before. It was the most powerful performance I had ever seen.

Here was this blind man on stage in such complete and utter command of his surroundings that I soon forgot about his blindness altogether. Between songs he deftly adjusted mic stands, rearranged his horns, and directed the rest of the band. He played his two saxophones at once and then tossed one aside when it was time for his tenor solo. He kept time with a foot cymbal and a large gong. He demolished a wooden chair and broke it into pieces and beat the stage with its remains.

In that instant, despite my stature as a recent college grad living in Texas who hadnÕt even written one article on jazzŃmy one published piece of music writing at that point was a small music review in a local paperŃI decided that I had to write a book about him. I would track down everyone who knew him while they were still alive, I would collect their stories of him in the hopes of preserving RahsaanÕs legacy.

***

Although my minor was in music, I had only begun to learn the history of jazz and blues. The jazz world seemed vast and daunting with those in the know constantly rattling off jazz trivia as though discussing the NFL. The entire surrounding culture seemed male-dominated, overly-intellectual, and like a secret club.

HereÕs where things get weird. I was writing about Rahsaan because he was calling to me. That longing to know him was so insatiable that I spent the next several years traveling around the country and beyond, scraping together just enough money and living on maxed out credit cards in the single-minded pursuit of hearing stories told by those who knew him.

This emotional quest led me from the basement of a London jazz club to his Ohio boyhood haunts and eventually to the bed where he once slept. This quest took on a serendipitous feel. Crucial leads would appear out of nowhere, coincidences became turning points, and I eventually began to trust what his widow Dorthaan had insisted from the first time I met her: ŅThere is some connection between you two.Ó Days after my first urge to write a book about Rahsaan, I found out heÕd died on my birthday, the day I turned four.

***

I soon learned he had this magical effect on every life he touched. Those closest to him felt moved by his spirit. Grown men broke down in tears telling me stories about him. A wisdom encircled Rahsaan that had folks believing he had something greater to say, something supreme to impart each time he spoke. Part southern preacher, part stand-up comic, part ancient-prophetŃRahsaanÕs voice boomed with authority with his words always aimed at delivering the most hard-hitting truths. ŅHe has the voice of a king,Ó someone once said.

***

Rahsaan never allowed obstacles, including blindness, to stand in his way. ŅIÕm a man, first. So-called blindness is secondary. I donÕt believe, that when I pick up an instrument, IÕm blind to anyone.Ó He never faltered in his conviction, even when faced with confounded critics who continually dismissed his genius as a circus act, a gimmick, or even a blind manÕs freak show.

Two years before he died Rahsaan suffered a debilitating stroke and lost the use of the right side of his body. Doctors told him that he would never play music again. After several months of therapy, it was clear that he would not regain the use of his right hand. Unstoppable even after this harshest blow, Rahsaan devised a way to play his horns with the use of only his left hand. ŅI felt that urgency,Ó he told an interviewer. Just nine months after his stroke, Rahsaan made a heroic comeback and continued to record and tour until his death.

Once you know Rahsaan, you begin believing anything is possible. Rahsaan not only showed me my path in life, he also gave me the courage to follow it. I set off at twenty-three: naive, unsure, and without a clue. All I had was the deepest longing I had ever felt and the haunting sounds of ŅThe Inflated TearÓ pursuing me. I had to know Rahsaan.

Review on Jazz Music Archives:

Rahsaan Roland Kirk and his music exist in a universe all their own, sure he may use some of the same tonalities and rhythms as fellow jazz and RnB musicians, and he can take things off the deep end at will much like his fellows in the avant-garde, but no one else sounds like Kirk. There is an unpretentious directness to RolandÕs music, a raw street level vibe that connects to the earliest days of New Orleans. You get the feeling that if Roland had not had a recording contract, he would have been out on some street corner playing the same music. ŅThe Inflated TearÓ is a great record, but donÕt expect a lot of fireworks, by Kirk standards ŅTearÓ is fairly laid back, but its not the least bit commercial, nor does Kirk hold back on his trademark personality and creativity.

Despite the uniqueness of KirkÕs music, some parallels to other artists can be drawn. His sometimes blunt approach can recall Sun Ra and Monk, his loose sound and massive tone on the tenor may remind some of John Gilmore and his ability to mix many eras of jazz into one musical approach recalls Mingus and Elllington. All of that is here on ŅInflated TearÓ, but this album is also a bit mellowed with a laid back 60s beatnik vibe, somewhere along the lines of early Herbie Mann and Eddie Harris.

The album opens with ŅThe Black and Crazy BluesÓ, a New Orleans dirge with modern elements which is followed by ŅA Laugh for RoryÓ, a fun upbeat cool jazz number on the flute(s). Some consider KirkÕs ability to play more than one instrument at a time to be a gimmick, but on ŅRoryÓ, and elsewhere on this album, he shows that his ability to harmonize the melody with simultaneous nose flute and concert flute is far more than a gimmick and adds some very interesting unique dimensions to his arrangements. The following tune, ŅMany BlessingsÓ, contains some explosive tenor work and side one closes with the pretty flute ballad, ŅFingers in the WindÓ.

Side two opens with the albumÕs title track. This piece is more like a musical/theatrical re-telling of how a nurse accidentally blinded Kirk for life at the age of two. This one is quite different from the rest of the album and features primitive sounds on three horns at once. Despite the heavy subject matter, this is hardly indulgent and adds to that singularity that is Rahsaan. After this opening, DukeŌs ŅThe Creole Love CallÓ follows and KirkÕs ability to harmonize on two horns works to good advantage as he uses EllingtonÕs transparent framework to include sounds of centuries past as well as the future. This one also features another strong, but short ride on the tenor. The album closes out with three bluesy hard bop numbers that show Kirk and his band working with short concise forms, no cliche gratuitous solos, everything compact and to the point with just enough solo to fit the tune. The closer, Lovellevelliloqui", has one of Kirk's best and quirkiest tenor solos on the album.

This is a great album, maybe not as far out as some of KirkÕs records, but possibly that makes this one a good first buy for somebody wanting to check out his music.

LP track listing

All songs written by Roland Kirk except as noted.

Side One

1. "The Black and Crazy Blues Š 6:07

2. "A Laugh for Rory" Š 2:54

3. "Many Blessings" Š 4:45

4. "Fingers in the Wind" Š 4:18

Side Two

5. "The Inflated Tear" Š 4:58

6. "The Creole Love Call" (Duke Ellington) Š 3:53

7. "A Handful of Fives" Š 2:42

8. "Fly by Night" Š 4:19

9. "Lovellevelliloqui" Š 4:17

Personnel:

* Roland Kirk Š tenor saxophone, manzello, stritch, clarinet, flute, whistle, cor anglais, flexafone

* Ron Burton Š piano

* Steve Novosel Š bass

* Jimmy Hopps Š drums

* Dick Griffith Š trombone