Thanks I'll Eat It Here

Studio album by Lowell George

Released 1979

Recorded 1979

Genre Rock

Length 31:19

Label Warner Bros

Producer Lowell George

Thanks, I'll Eat it Here is the title of the only solo album by the late rock and roll singer-songwriter Lowell George.

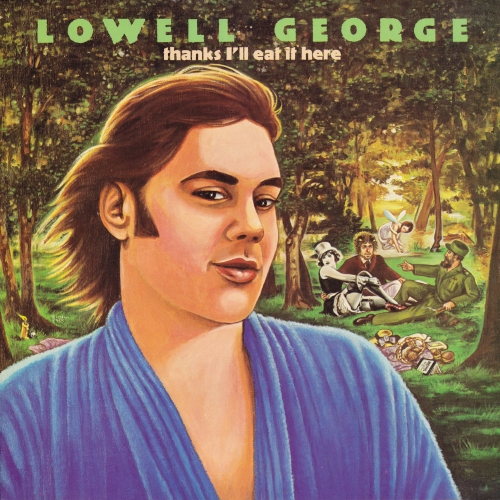

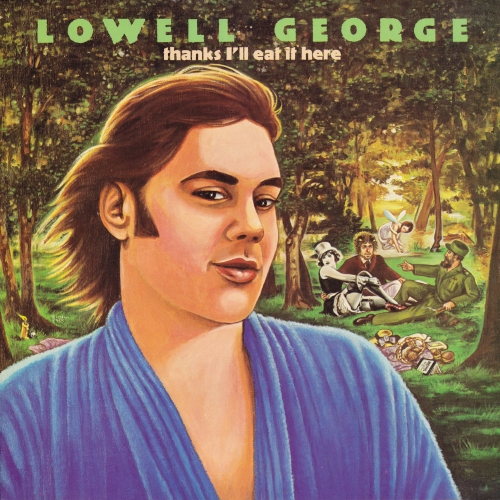

While George is best known for his work with Little Feat, by 1977 Lowell felt that they were moving increasingly into jazz-rock, a form in which he felt little interest. As a result, he began working on his own album. Thanks I'll Eat it Here is an eclectic mix of styles reminiscent of Little Feat's earlier albums - in particular Dixie Chicken, on which the track Two Trains originally appeared. The album was released just before the death of Lowell George in 1979 and has cover art by Neon Park (a feature of almost all Little Feat albums) containing several pop-/cult references including a picnic scene, mirroring Edouard Manet's "Le déjeuner sur l'herbe", which shows Bob Dylan, Fidel Castro and Marlene Dietrich as Der Blaue Engel with an open copy of Howl beside them.

Professional ratings

allmusic 4.5/5 stars

Review by Stephen Thomas Erlewine of allmusic:

Thanks I'll Eat it Here is strikingly different from the fusion-leanings of Little Feat's last studio album, Time Loves a Hero. Lowell George never cared for jazz-fusion, so it should be little surprise that there's none to be heard on Thanks. Instead, he picks up where Dixie Chicken left off (he even reworks that album's standout "Two Trains"), turning in a laid-back, organic collection of tunes equal parts New Orleans R&B, country, sophisticated blues, and pop. George wasn't in good health during the sessions for Thanks, which you wouldn't tell by his engaging performances, but from the lack of new tunes. Out of the nine songs on the album, only three are originals, and they're all collaborations. That's a drawback only in retrospect -- it's hard not to wish that the last album George completed had more of his own songs -- but Lowell was a first-rate interpreter, so even covers of Allen Toussaint ("What Do You Want the Girl to Do"), Ann Peebles ("I Can't Stand the Rain") and Rickie Lee Jones ("Easy Money") wind up sounding of piece with the original songs. George's music rolls so easy, the album can seem a little slight at first, but it winds up being a real charmer. Yes, a few songs drift by and, yes, Jimmy Webb's vaudevellian "Himmler's Ring" feels terribly out of place, but Lowell's style is so distinctive and his performances so soulful, it's hard not to like this record if you've ever had a fondness for Little Feat. After all, it's earthier and more satisfying than any Feat album since Feats Don't Fail Me Now and it has the absolutely gorgeous "20 Million Things," the last great song George ever wrote.

Review by Gordon Hauptfleisch of blogcritics:

The death of a musical artist, whether of the emerging or the resurgent kind, seems especially unfortunate if you’ve seen him or her in person not too long before the demise. Because I had seen, as a kid back in 1966, a lively and spirited Bobby Fuller (“I Fought The Law,” "Let Her Dance") in an in-store appearance a few weeks before he was mysteriously found dead in a parked car in Hollywood, I personally found the controversial "suicide" theory implausible. And in seeing Roy Orbison in concert at the Arizona State Fair in 1988, a few months before he died of a heart attack, I shared a virtually communal experience with an audience of well-wishers happy to see a deserving pioneer in a triumphant comeback not only with the Traveling Wilburys but also with new solo album, Mystery Girl.

Lowell George, founding member and leading light of Little Feat, also succumbed to a fatal heart attack, in 1979, just as he was embarking on a promising solo career. While I didn’t see any of his early solo performances, I did catch one of the last Little Feat concerts — in their original incarnation — the year before at Santa Barbara’s Arlington Theater, just a two-block walk from where I lived at the time. It was a potent mix of the jazz-fusion direction of latter-day Little Feat and earlier George-led Dixie Chicken-style Feat - the eclectic retention of funk, R&B, country, blues, and pop that marked and was upheld in George’s first and only solo LP.

Indeed, Thanks I’ll Eat It Here sustains the lingering and bittersweet memories of that last show with an alternately celebratory and melancholic collection of songs that spotlights the soulful and silky fluidity of George’s vocals. That smooth sublimity is at a zenith in a cover of Allen Toussaint’s “What Do You Want The Girl To Do” and Ann Peebles’ “Can’t Stand The Rain.” A little more spunk and fun is found in Rickie Lee Jones’ “Easy Money,” while the off-kilter novelty of Jimmy Webb’s “Himmler’s Ring” adds a little vaudevillian spice to the variety.

But George shows he's more than a fine interpreter of some choice material. In addition to a punchy reprise of “Two Trains” from Dixie Chicken, George had a hand in writing or co-writing some other highlights, including the horn-backed, funky-but-chic “Honest Man,” and the quirky south-of-the-border tale “Cheek To Cheek.” The stand-out track, however, is the affecting “20 Million Things,” which wistfully reminds us of the distracting and transitory nature of life:

If it's fix a fence, fender dents

I've got lots of experience

Rent gets spent

And all the letters never written don't get sent

It comes from confusion, all things I left undone

It comes from moment to moment, day to day

Time seems to slip away...

In effect - moment to moment, track to track - Thanks I’ll Eat It Here helps recapture a little of the time that slipped too easily away with Lowell George's death, though it must leave behind "all things [he] left undone."

http://blogcritics.org/music/article/vinyl-tap-lowell-george-thanks-ill/

Biographical information by JP Gelinas of Perfect Sound Forever:

Best remembered as the de facto leader of the classic American rock band, Little Feat, Lowell George's distinctive style of slide guitar and vocalizing helped create a style of music that was a unique blend of second-line funk, gospel, Chicago blues, jazz and country balladry that still stands today as one of the most unique developments in American popular music during the 1970's.

George was born in Hollywood, California on April 13, 1945. His father, Willard, was a prominent furrier to many Hollywood movie stars and the family's close friends included such notables as Errol Flynn and W.C. Fields. One can only imagine the deep influence that a character like W.C. Fields must have had on a young Lowell George. It's interesting to note that, throughout his career, Lowell George displayed a sense of humor that lent an air of surreal spontaneity to his music. This element of humor crops up in the multi-syllabic wordplay of George's song lyrics and on Little Feat's offbeat album covers that featured the bizarre and often comic artwork of the artist Neon Park. Van Dyke Parks, in The Little Feat Saga, Bud Scoppa's informal biography that was part of the definitive Little Feat CD box set, Hotcakes & Outtakes, states that, "Lowell was an absurdist. He would do things for the wrong reasons. I think he had the audacity of a schizophrenic, which I associate with great work, whether it's Van Gogh or Ravel. "Fatman in the Bathtub" –that's Cartoon Consciousness. You see the physical comedy in Lowell George that you get out of Buster Keaton. It's the tragicomedy of man in crisis – that's what Lowell did..."

At an early age, George's interest in music was encouraged by his mother, Florence, who was an accomplished pianist. Lowell's first instrument of choice was the harmonica which he took up when he was five years old. His first public musical performance was on the locally televised Al Davis Talent Show where he played a harmonica duet with his brother Hampton. Also appearing on the same show was another young musician named Frank Zappa. Apparently, both Zappa and the George brothers lost out to a girl tap dancer.

Lowell attended Hollywood High where his classmates included Paul Barrere (later to become the rhythm guitarist in Little Feat), his future wife Elizabeth and Martin Kibbee, who went on to be a lifelong friend and co-writer with George of such Little Feat classics as "Fatman In The Bathtub," "Dixie Chicken" and "Rock and Roll Doctor." Around this time, George's brother departed for a stint in the army, leaving behind a classical guitar that the enterprising Lowell soon mastered. George also became proficient on a number of other instruments as well; the banjo, clarinet and a Japanese bamboo flute known as the shakuhnachi. Within the next two years, Lowell would also study a popular sixties instrument known as the sitar at a Los Angeles school run by Ravi Shankar. In some of Lowell's work with Little Feat, such as "The Fan," one can detect traces of Middle Eastern music so his studies under Shankar seemed to have had a lingering effect on his musical sensibility.

By the end of high school, George's interest had turned to jazz. Martin Kibbee, in Mark Brend's comprehensive biography of Lowell George Rock And Roll Doctor (Backbeat Books, 2002), describes Lowell's developing love for music, "His taste in music at that time ran more to West Coast Jazz than, say, Jan and Dean or the Beach Boys. Les McCann and Mose Allison were appearing at Sunset Strip clubs like The Bit and The Renaissance where we hung out. Lowell wore a black turtleneck, the whole beatnik bit…"

Following high school, George attended Valley Junior College where he studied art history. While attending college, George held a job as a gas station attendant. In later years, he credited this experience with providing the inspiration for his future country styled trucker anthem "Willin" which is, perhaps, the most widely known Lowell George song. By the mid-Sixties, George had purchased a Fender electric guitar and an amplifier. After seeing the Byrds perform at The Brave New World coffeehouse, he decided to form his first band, The Factory.

In Rock & Roll Doctor, Brend describes the Los Angeles music scene that confronted the young musician: "In the mid-1960's, the United States was teeming with newly formed young bands.. It was against this backdrop that countless young Americans grouped together in garages, plugged their Fender Mustang guitars into Vox amplifiers and ripped through 'Hey Joe'… Most of these so-called garage bands were musical primitives with more enthusiasm than dexterity, destined to play their local circuit for awhile and maybe record a demo that would appear on a collector's compilation decades later..."

The Factory was Lowell George's first serious attempt at carving out a career for himself in the music business. Consisting of Martin Kibbee (bass), Martin Klein (guitar), Richie Hayward (drums) and Lowell George (guitar, lead vocals and assorted instruments such as flute and clarinet), the band soon established itself on the Los Angeles rock club circuit. As to what this group sounded like, the best existing artifact to check out is Lightning Rod Man, a collection of tracks recorded for the Uni label in 1966. As evidenced by such tracks as "Lost," "Candy Cane Madness" and "Smile, Let Your Life Begin," the music of The Factory reflects a late-sixties folk-punk rock style as championed by such LA bands as Love, The Music Machine and The Seeds.

Towards the end of 1967, things were winding down for The Factory. They had been a mainstay of the club scene and had even appeared in episodes of the popular television sit-coms F-Troop and Gomer Pyle but they had failed to create any hit records. One of their last projects was to record two demo songs for the Original Sound record label that were produced by Frank Zappa. These two tracks, "Lightning Rod Man" and "The Loved One" (both included on the Lightning Rod Man CD) contain familiar Zappa production elements. Actually, it is on the track, "Lightning Rod Man," that Lowell George hits his first serious stride as a musician. Written by George and Kibbee and based on a Herman Melville short story, "Lightning Rod Man" finds George delivering a tour de force vocal in a style that recalls the early work of Captain Beefheart. In fact, before this track had been properly identified as a recording by The Factory, many collectors assumed it was a rare Captain Beefheart outtake. George's brief time in the studio with Zappa apparently had quite an influence on the young musician as his later work as a producer of Little Feat records would indicate. Like Zappa, he adopted studio work habits that involved staying in the studio for several nights running and not leaving until a particular track was finished to his satisfaction.

While the remaining members of The Factory formed a new band called The Fraternity of Man, George found himself working as a hired gun for The Standells, who were running out their proverbial 15 minutes of fame after the success of their hit "Dirty Water." In a 1975 interview in Zig Zag magazine, George described his experience with The Standells, "I replaced Dicky Dodds, the lead singer. …he quit because he couldn't stand it. And I finally quit because I couldn't stand it either." In his typical style of going from one extreme to another, George left The Standells to become a member of Frank Zappa's Mothers of Invention, the most cutting edge rock band at that time.

Lowell's brief tenure in The Mothers lasted about a year. While George expressed his frustration at working within the strict framework of Frank Zappa's musical vision, it seems that he did come away with the firm knowledge of how to be a bandleader. Brend explains in his book how George's time in the Mothers of Invention provided him with a template for how he would run his future band, Little Feat: "George saw in Zappa's management of the Mothers a model of how a band could be run. It was a model that worked, that was productive, and that allowed for individual creativity – but within the clear boundaries set by the bandleader. This idea of how things might be was to stay with him throughout his career."

Another important influence that Zappa had on Lowell George was in song composition. While in the studio with the Mothers, George no doubt witnessed Zappa's penchant for cutting up various musical parts and splicing these taped elements together, thereby creating entirely new song sections. George would go on to adapt this style of songwriting within a short time. On more than one occasion, George would refer to his songs as "cracked mosaics." Years later, in a 1975 interview in Zig Zag magazine, George would state, "I use tape like someone would use manuscript paper." All of this sheds light on how crucial George considered the recording studio as an essential tool that was needed for songwriting. Like Zappa, George eventually got so comfortable in the recording studio that he would create spontaneously, no matter how long the sessions ran and no matter how much the end result cost. These work habits would have a serious impact on Lowell's health towards the end of his brief life.

After touring and participating in several recording sessions, it is unclear whether Lowell was asked to leave the band because of Zappa's intolerance for drug use or if the young guitarist had just felt it was time to leave and start another band. At this time, George had also composed one of his best known songs, "Willin" and, as a tape of the song was circulated among various record labels, Lowell began receiving offers to make his own record. In any event, George departed The Mothers just prior to their 1969 tour of Europe. His musical contributions to this era of The Mothers of Invention are featured on the albums Weasels Ripped My Flesh and Burnt Weenie Sandwich.

The confluence of events of the past year had set the stage for the formation of Little Feat; George had previously worked with drummer Richie Hayward in The Factory, he had met and played with Mothers' bassist Roy Estrada and the final piece of the musical puzzle fell into place when he struck up a friendship with Bill Payne, a talented young piano player who had been hanging around Zappa's office. In The Little Feat Saga, Payne describes the ideas that he and George shared concerning the musical direction of their new band, "We talked about the kind of band we wanted it to be. Should we have a horn section? What should the bass player play? Are we going to relegate ourselves to one style of music? We decided there shouldn't be any limits to what we would do. If we wanted to play a waltz, great. If we wanted to play a straight-ahead song, fine." This mindset is obviously one of the key ingredients that led to the many stylistic innovations that characterized the music of Little Feat.

As the 1970's began, the music scene began to change. A less-is-more approach replaced the extended jam format popularized by such bands as Cream and Iron Butterfly. The Byrds cut their seminal country rock opus Sweetheart of the Rodeo, Dylan released the mellow Nashville Skyline, and Gram Parsons formed The Flying Burrito Brothers. The most important group of this period was Bob Dylan's former backing combo, The Band, whose Music from Big Pink literally redefined popular music overnight. In the midst of all of this, after submitting a demo tape of "Willin" to Lenny Waronker of Warner Brothers, Little Feat was signed to a recording contract. They joined a roster of such eclectic artists as Arlo Guthrie, Van Dyke Parks, The Youngbloods, Deep Purple, James Taylor, Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell, The Fugs and Neil Young.

The Little Feat album contained a wide variety of musical influences. Among the various styles represented on this first album are country rock ("Strawberry Flats"), mid-tempo FM radio rock ("Hamburger Midnight Blues"), tinges of lysergic psychedelia ("The Brides of Jesus" and "Got No Shadow") as well as the Howlin Wolf covers, "44 Blues" and "How Many More Years." I consider these last two tracks to be some of the most important recordings in the Lowell George canon. They reveal the most primal of George's musical influences. Howlin' Wolf proved to be such a consistent presence within George's music that Lowell would soon compose his own version of a Howlin Wolf song ("Apolitical Blues") and, if you listen closely, you can detect the Chicago blues style of Wolf sprinkled throughout many Little Feat recordings. In addition to these benchmark tracks, the album is notable for producing the first of many versions of Lowell's country rock classic, "Willin." In another example of his developing obsessive qualities in the recording studio, George would insist on including different versions of "Willin" on various Little Feat albums. While Little Feat had a sparse quality about it, some of the enduring musical elements that defined Little Feat were already in place in the form of Payne's effervescent keyboard work, George's unique singing style as well as his slide guitar work.

The story of how Lowell George came to develop his unique style of playing slide guitar has a mythical quality about it that stands as a good example of just how accomplished a musician he had become by this point in time. The day before Lowell was supposed to start recording his guitar parts for the first Little Feat album, he was sitting at his kitchen table pursuing one of his lifelong passions – working on model airplanes. While adjusting the motor in one of the planes, he sliced open his hand on the tiny propeller. Since the hand that he injured was the one that he used to pick out notes on his guitar, he opted to employ the slide guitar style while overdubbing most of his guitar parts for the record. Rick Harper, Lowell's close friend and road manager, sheds more light on this incident in The Little Feat Saga, "He never told anybody... he'd lost the feeling in two or three of his fingers. He said at first it was like marshmallow and he couldn't tell how much pressure to put on the strings." It is indeed remarkable that George was able to overcome the results of his accident and discover a new way of expressing himself musically.

George had already dabbled in this style of playing guitar while with the Mothers of Invention but being forced to play using a slide for an extended period of time while his hand was healing probably led to the discovery of his own singular style of slide guitar playing. Lowell quickly developed his own "sound" which featured clean compressed notes played with precision and filled with sustain. Along with Lowell's unique slide guitar, he was also developing a distinctive vocal style which employed the technique of melissima by which the singer melodically embellishes certain syllables within a phase. This style of singing, much like Lowell's slide guitar, would become a critical element of Little Feat's musical identity.

While the first Little Feat album did a good job of illustrating the talents within the band, it sold poorly and the group was in danger of being dropped from the Warner Brothers label. Fortunately, Van Dyke Parks interceded on their behalf and convinced the label executives to let the band record a second album. Recording on their sophomore effort, which was initially supposed to be titled Thanks I'll Eat It Here but later changed to Sailin' Shoes, began in the spring of 1971. The album indicates how quickly Little Feat was developing musically. The record features two songs ("Trouble" and "Texas Rose Cafe") that reflect George's absurdist sense of humor. Among the record's other highlights are Lowell's homage to Howlin' Wolf ("Apolitical Blues") and the anthemic "Tripe Face Boogie" which features the most incendiary slide guitar solo ever recorded by George. During this solo, Lowell's technique with the slide is electrifying as he coaxes a series of high piercing notes on his guitar.

As George's musical ability developed, so did his ideas on how his music should be presented to the public. The Sailin' Shoes record marks the debut of the distinctive Little Feat "look" which was created by the experimental artist, Neon Park. George had been exposed to Park's art while in the Mothers of Invention. Park created the infamous Weasels Ripped My Flesh cover on which a man is depicted using a live weasel to shave his face. Park's sense of absurd imagery appealed to George's own innate sense of dada art. The Sailin' Shoes cover, depicting a slice of cake on a swing, a phallic snail and a Mick Jagger inspired image of Gainsborough's Blue Boy, caused quite a stir upon the album's release. Starting with this second album, Park's art would adorn every subsequent Little Feat album cover and, even though Park passed away in 1993, his surrealistic imagery continues to be featured on every Little Feat record that is released to this day.

In addition to his work with Little Feat, George began to be in demand as a session player and producer on many recording projects by other artists. The extensive list of records that Lowell George lent his talents to is considerable. Among some of his finest work outside of Little Feat can be found on such albums by such artists as John Sebastian, John Cale, Bonnie Raitt, Van Dyke Parks, Robert Palmer, and Valerie Carter. Many of the musical elements that Lowell brought to these projects would later surface on his own solo album, Thanks I'll Eat It Here.

Besides his appearances on albums by well known artists, George was fond of being a mentor to many young musicians who were just starting out in the business. He would frequently use his considerable reputation to help these fledgling musicians get their first break. One such example of this is his support of Ricki Lee Jones during the early stages of her career. George graciously recorded a cover version of her song "Easy Money" in an effort to get her signed to the Warner Brothers label. Another case of this type of mentorship can be found in his active involvement on Valerie Carter's 1977 album, Just A Stone's Throw Away. Carter, largely unknown in the business at the time, was impressed with the extensive work George did on her record. George co-wrote four songs ("Heartache," "Face Of Appalachia," "Cowboy Angel" and "Back To Blue Some More") as well as co-producing several tracks. This type of generous behavior on the part of Lowell George became legendary among the Los Angeles musical community.

Sometime in early 1972, bassist Roy Estrada, frustrated by the band's lack of commercial success, left Little Feat and returned to the Mothers of Invention. For a time, George busied himself with session work on Van Dyke Parks' calypso infused album, Discover America. As these sessions wound down, Lowell began to consider the musical direction of Little Feat. In a bold move, George essentially re-invented the sound of Little Feat by adding three new members; Kenny Gradney (bass), Sam Clayton (percussion) and Paul Barrere (guitar). Gradney and Clayton joined with drummer Richie Hayward to become one of the most renowned rhythm sections in rock & roll and gave the new line-up a funky sound that recalled the great New Orleans band, The Meters. It is the addition of Paul Barrere, though, that gave the band more depth as his presence on rhythm guitar allowed Lowell George to concentrate on his developing slide guitar technique. This line-up of Little Feat would remain in place until Lowell George's death in 1979.

In late 1972, the restructured line-up released its first album. Along with expanding the band's creative boundaries by adding some new members, George somehow talked his record label into letting him produce Dixie Chicken. The record broke new ground with its mélange of swamp funk, acoustic balladry, country and jazz sounds. The album's title cut, a George/Kibbee song which features a convoluted tale of drunken misadventure, and the humorous "Fatman in the Bathtub" still stand as some of Little Feat's best recorded works. The Dixie Chicken album became a turning point for the band as a newfound assuredness in the studio inspired an increased confidence on stage.

Along with his touring commitments with Little Feat, George began to increase his session work. Around this time he appeared on albums by the soul singer Kathy Dalton and former Velvet Underground member, John Cale. Cale's album, Paris 1919, uses George's talents on acoustic and slide guitar to great effect.

With the increased success of Little Feat as a touring band, Lowell George began to experience personal difficulties as he began to depend on liquor and drugs to help him deal with the pressure of being the bandleader, head songwriter, record producer as well as lead singer of Little Feat. His lifestyle was also beginning to impact his relationship with the band. In Rock & Roll Doctor, Mark Brend describes George's growing inability to deal with the creative compromises he was forced to make within the framework of the newly expanded band line-up, "The consequences of his desire to collaborate and his restlessly creative nature can also be seen in the circumstances surrounding Little Feat at this time. The expanded line-up that George had put together as a means to develop creatively ultimately proved to be his undoing. He needed collaborators… and they had to be of a high standard of musical ability. But he only wanted collaboration up to a point, because he also wanted ultimate control. Yet players as talented as Barrere and Payne were never going to be content with being sidemen to a dominant figure… Eventually the collective weight of opinion in the band was to turn against George."

During 1974, after the Dixie Chicken album experienced poor record sales, Little Feat broke up for a brief period. George suggested that the band members go their separate ways and pursue session work until he could renegotiate a better contract with Warner Brothers. One of the projects that Lowell was involved with at this time was his participation in the recording of the Mike Auldridge album, Bluegrass & Blues (1974, Takoma Records). Auldridge, an accomplished dobro player, impressed George with his slide technique. Elements of bluegrass music that recalled these recording sessions would later surface on Thanks I'll Eat It Here. During this hiatus from Little Feat, George also contributed his musical and production talents to Bonnie Raitt's Takin' My Time and John Sebastian's Tarzana Kid. His work on Sebastian's record, particularly on the track "The Face of Appalachia" which he co-wrote with Sebastian, is comparable to the quality of his best Little Feat work.

During this same period, Bill Payne landed a gig with the Doobie Brothers and Lowell, along with several of the other members of Little Feat, journeyed down to New Orleans where they were involved in the recording of British R&B singer Robert Palmer's Sneakin' Sally Through The Alley album. Lowell's exposure to the musical culture of the Big Easy would quickly emerge as a primary influence on Little Feat's fourth album, Feets Don't Fail Me Now; a record that extends the funky groove of the Dixie Chicken album as the band conjures up such syncopated classics as "Spanish Moon," "Skin it Back," and the title track. The real highlight of the album is "Rock & Roll Doctor," a George/Kibbee song that delivers a dynamic Lowell George vocal performance that employs a feverish call and response gospel technique as George's slide guitar is coupled to great effect with the second line rhythms of New Orleans.

As much as Dixie Chicken and Feets Don't Fail Me Now established a new direction for the band, 1975's The Last Record Album found George struggling to produce a piece of commercially viable product. While the trademark Little Feat sound is present, many of the tracks seem to reflect the growing obsessive behavior that Lowell was exhibiting in these all-night recording sessions as he searched for sounds that would produce the perfect hit record. Also noticeable is the increased songwriting and vocalizing by both Paul Barrere and Bill Payne. In his book, Mark Brend presents a clear picture of the situation, "George's artistic energy declined and, crucially, his ability to write great songs seems to have greatly diminished. Within another year, Lowell George would no longer be the leader of Little Feat." Another example of George's growing obsessive behavior in the recording studio is the sound of The Last Record Album, which has a tight, compressed quality about it that hints at Lowell's penchant for endless overdubbing tracks in search of perfection. The album's best moment occurs when George delivers his poignant ballad, "Long Distance Love" which features the singer ruminating on the rigors of touring and the damage that the lifestyle of a working musician can imprint on personal relationships.

George's daily use of drugs and alcohol finally caught up with him in 1978 when he contracted hepatitis and was not able to attend the band's initial recording sessions for Time Loves A Hero. With the recording sessions in shambles, Payne and Barrere called in Ted Templeton, who had previously handled the production duties on the band's second record, Sailin' Shoes, to replace George as the album's producer. Templeton, in The Little Feat Saga, explains some of the problems George was having during these recording sessions, "Lowell kind of distanced himself on that record... When we did 'Rocket in my Pocket'... it came time for the solo, he called and said, 'I can't do it today. I'm sleeping in.' So I called Bonnie Raitt and she came down and played a fucking killer solo. So I called Lowell and said 'Listen to this. What do you think? Doesn't this burn?' He actually got out of bed and came down and played the solo..." Incidents like this give further evidence to the dangerous impact that Lowell's lifestyle was having on his ability to make music.

Although George does indeed bring this record to life with his only solo songwriting contribution, "Rocket in My Pocket," Time Loves A Hero is devoid of the engaging musicality that characterized every other Little Feat album up to this point. One track, "Day At The Dog Races," revealed the artistic chasm that had developed between Lowell George and the rest of the band. The song is primarily based in the style of the mid-seventies jazz fusion band, Return To Forever. In The Little Feat Saga, producer Ted Templeton describes Lowell's reaction to this departure from the band's trademark sound, "Lowell was a little upset. He said, 'What is this, fucking Weather Report?'" Upon its release, Time Loves A Hero was considered by the press and public alike to be a major disappointment.

Little Feat's musical credibility was restored somewhat with the 1978 release of the band's first official live album, Waiting For Columbus which saw George restored to his role as the band's producer. The album does an excellent job of capturing the onstage improvisational interplay that characterized many of Little Feat's best concerts. George, in particular, brings a renewed sense of energy to his singing and playing. Little Feat's first live album also produced the first credible record sales of the band's career. For the moment, Waiting For Columbus provided a sense of vindication for Lowell George.

George maintained an extremely busy schedule towards the end of 1978. Besides touring with Little Feat, he was involved in production work on his first solo album as well as producing sessions for Shakedown Street, the next album by the venerable San Francisco jam band, The Grateful Dead. Working with The Dead should have been a window of opportunity for George to establish a more viable musical identity outside of Little Feat and yet the record reeks of mediocrity. Sadly, Shakedown Street stands as one of the worst albums ever released by The Grateful Dead. In Rock & Roll Doctor, Brend explains that, "Although things started well, the project ran out of steam after a few weeks and George withdrew from the sessions before the album was finished. Explanations for this were not forthcoming but no doubt George's perfectionism was at odds with the laidback Grateful Dead approach." I have had the opportunity to hear an outtake of the "Good Lovin" track from this album which surprisingly features Lowell George singing the lead vocal part. His voice is extremely energetic on this version and the contrast between this outtake and the version featuring the weaker vocals of Bob Weir, Jerry Garcia and company that was eventually released is stunning, to say the least. The "Good Lovin" outtake hints at just how good this project could have been had if George had managed to summon the needed energy to finish the production. It was a clear indication that his years of substance abuse had finally begun to impact his musical judgment as a producer and musician. The only positive thing that Lowell seemed to take away from this project was "Six Feet of Snow," a sprightly country tune he co-wrote with Keith Godchaux, keyboard player for The Dead. This song would make an appearance on George's last album with Little Feat, Down On The Farm.

While much of the rancor between Lowell George and the rest of Little Feat had temporarily subsided due to the success of Waiting For Columbus, work on the next album reawakened some of the problems the band had been having during the production of Time Loves A Hero. George would waste countless hours of expensive studio time doing endless retakes of the same material as he drove everybody crazy with his obsessive behavior, always searching for a perfect take. Suddenly, in the midst of the chaotic recording sessions, George lost all interest in working on Down On The Farm. Instead, he turned his attention to finishing Thanks I'll Eat It Here. This infuriated the rest of the band and a permanent split within Little Feat seemed imminent. Down On The Farm would end up being released shortly after the death of Lowell George.

Thanks I'll Eat It Here was a project that Lowell had dabbled with, off and on, since 1975. The current problems he was having with Little Feat seemed to provide George with the impetus to complete this long awaited album. While George's solo record is often dismissed as an incomplete album that suffers from an overabundance of divergent styles of music, I personally find that it offers up the most intimate portrait of Lowell George's true musical personality on record. Lowell's debut solo record presents a heady mixture of soul, country, folk, mariachi band music and the familiar swamp funk of Little Feat, backed up by Bonnie Raitt and the cream of the 70's studio musicians crop (Nicky Hopkins, Jim Keltner). His masterful vocal work on the blue-eyed soul songs, "What Do You Want The Girl To Do" and "I Can't Stand The Rain," stands as the most accomplished singing of his career. The serene acoustic ballad, "20 Million Things To Do," recalls the elegant "Long Distance Love" from The Last Record Album and shows that Lowell still had some substantial music left in him.

In an effort to promote the album, Lowell embarked on a small U.S. tour. I was fortunate enough to catch one of these shows at The Bottom Line in New York. Despite whatever problems Lowell George had been dealing with as a songwriter and record producer, Lowell George's live show was filled with an urgent energy and charisma that had been missing from the recent Little Feat shows that I'd witnessed. I noticed that his vocal work had taken on a slightly smoother quality and his passionate phrasing seemed very precise; almost as if a great deal of thought had gone into thinking about exactly how these new songs should be sung. The only element that seemed to be missing was a sense of camaraderie between George and his band, which was largely made up of L.A. session players. At the end of this show, as George returned to the stage for the final encore he intoned, "This is the only other song we know…" as the band went into a version of "Lafayette Railroad," an instrumental off of the Dixie Chicken album. It was indeed a transcendent moment as the sound of Lowell's mournful slide guitar filled the room. On June 29, 1979, while on a tour stop in Washington D.C., Lowell George died from a heart attack after staying up all night while working on a tape for an upcoming radio show to promote his solo record.

The news of Lowell George's death at the age of 34 brought forth a flood of tributes from the musical community. Bonnie Raitt referred to Lowell as the "Thelonious Monk of Rock & Roll." Neon Park evaluated his old friend's music by saying, "The thing that showed in his music: building networks of supreme logic then inserting key moments of insanity." Martin Kibbee, in Scoppa's biography, summed up Lowell's unique contribution to music, "Perhaps the most important thing Lowell achieved was a seamless blend of his Hollywood/white-boy irony with a totally black musical sensibility."

Shortly after George's death, Warner Brothers released Down On The Farm. While the record has an overall unfinished quality about it, are a few bright moments that recall Lowell's finest moments. As on Thanks I'll Eat It Here, his vocal work seems to achieve new heights of sophistication, particularly on the tracks "Perfect Imperfection," "Front Page News," "Be One Now" and "Six Feet Of Snow". His work on these songs, along with the material from his solo record, provide us with a brief glimpse of where his music was headed; a mature synthesis of country, blues and soul.

In the years after George's death, many archival recordings have been released by Little Feat. The best of these can be found on the 1990 collection, Hoy Hoy, and the box set, Hotcakes & Outtakes: 30 Years Of Little Feat.

As a final absurd word on Lowell George, I'll turn to guitarist Fred Tackett, who was part of George's backing band on the Thanks I'll Eat It Here tour and is presently a member of the present day line-up of Little Feat. In The Little Feat Saga, he recalls one night on the solo tour shortly before George's death, "We were driving down the New Jersey Turnpike in this bus and we stopped at this pizza joint off the highway. Everybody in the band shared a cheese pizza but Lowell bought a large pizza with everything on it, carried it to the back of the bus, and he ate the entire pizza by himself. He died two or three days later. So, when people ask me, 'What really killed Lowell?' I say, 'It was a pizza on the New Jersey Turnpike.'"

https://docs.google.com/View?id=dgrxgvp8_2f33ng4f7

LP track listing

Side One

1. "What Do You Want the Girl to Do" (Allen Toussaint)– 4:46

2. "Honest Man" (Lowell George, Fred Tackett) – 3:45

3. "Two Trains" (Lowell George) – 4:32

4. "Can't Stand the Rain" (Ann Peebles) – 3:21

Side Two

5. "Cheek to Cheek" (Lowell George, Van Dyke Parks, Martin Kibbee) – 2:23

6. "Easy Money" (Rickie Lee Jones) – 3:29

7. "Twenty Million Things" (Lowell George, Jed Levy) – 2:50

8. "Find a River" (Fred Tackett) – 3:45

9. "Himmler's Ring" (Jimmy Webb) – 2:28

Personnel

* Lowell George - guitar, vocals

* Bonnie Raitt - vocals

* James Newton Howard - keyboards

* Chuck Rainey - bass

* Denny Christianson - keyboards

* David Foster - keyboards

* Chilli Charles - drums

* Nicky Hopkins - keyboards, horn

* Jim Price - horn

* Jim Keltner - drums

* Jim Gordon - drums

* Michael Baird - drums, bass

* Dennis Belfield - bass

* Bobby Bruce - violin, guitar

* Turner Stephen Bruton - guitar, horn

* Dennis Christianson - horn

* Luis Damian - guitar & keyboards

* Gordon DeWitte - keyboards, piano

* Maxine Dixon - piano

* Arthur Gerst - piano

* Jimmy Greenspoon - guitar, piano

* Roberto Gutierrez - vocals, guitar, drums

* Richie Hayward - drums

* Jerry Jumonville - saxophone, guitar

* Ron Koss - guitar

* Darrell Leonard - horn, vocals

* Maxayn Lewis - vocals

* David Paich - drums

* Jeff Porcaro - drums, guitar

* Dean Parks - guitar & keyboards

* Bruce Paulson - keyboards

* Bill Payne - keyboards, vocals

* Herb Pedersen - vocals

* Joel Peskin - vocals, saxophone

* John Phillips - saxophone, drums

* Peggy Sandvig, Jim Self - drums

* Floyd Sneed - drums, vocals

* J.D. Souther - bass, vocals

* Paul Stallworth - bass, guitar

* Fred Tackett - guitar, vocals

* Maxine Willard Waters - vocals