- Format: MP3

Archive r&b studio sessions from 1965.

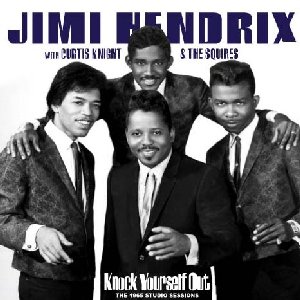

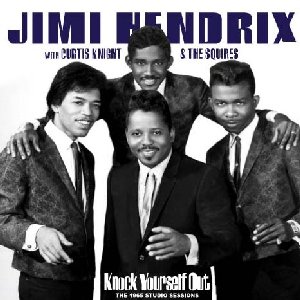

By September 1965, Jimi had completed stints as guitar-for-hire with the Isley Brothers, Little Richard and others. His next was with Curtis Knight, who gave the broke guitarist a guitar as a welcome incentive to play in his band, The Squires. Jimi remained with Curtis's band for nine months, until just before Chas Chandler discovered him.

Contained on this album are the two studio sessions that took place in October and December 1965. They spawned two singles, included here as the first four tracks. The band's fare of mid-sixties r&b, in a style with Stax and 60's pop leanings, has Jimi's guitar very much to the fore.

Curtis valued Jimi greatly; when he played live, he gave over much of the set to his prodigious new guitarist. In between Curtis numbers and 60's pop covers, showman Jimi would come forward and perform the blues (as heard on previous Jungle release 'Drivin' South'). Jimi and Curtis signed a recording contract with Ed Chalpin, who made these recordings.

This is the first time these 1965 studio tracks have been put together - previous exploitative releases have mixed them up with later recordings including many tracks where Jimi only played bass, gaining nothing but a poor reputation. This album redresses the balance, giving a fascinating and intriguing insight into the early Jimi Hendrix at work just months before his discovery.

With informed sleeve-notes by author and guitarist ex-Only Ones John Perry in a 12-page booklet, this mid-price CD package is very attractive to both fans of the Sixties and the many devoted connoisseurs of Jimi Hendrix's music.

Notes by John Perry.

Today, it's almost impossible to imagine the impact that Jimi Hendrix made when he first appeared in England. The sounds he created have been copied so extensively they’ve become an accepted part of the musical landscape and more or less taken for granted -- few people can remember a time when they weren't there.

Hendrix’s licks have been imitated, sampled, and endlessly recycled but never, as yet, improved upon. Nor are they likely to be unless somebody, born with the same natural skills, gets a chance to sharpen them playing R&B rhythm guitar on some C21st equivalent of the chitlin circuit. The roots of everything Hendrix went on to do with the Experience lie either in the discipline and timing he acquired touring and recording with bands such as the Isley Brothers, Little Richard, and the Kingpins (King Curtis’s combo, which included Cornell Dupree on guitar and Bernard Purdie on drums) or in his reaction against that discipline and timing.

But there was a time when both the man and the sound of his guitar were unknown. Hendrix was a natural star of such magnitude that those days didn't last long, although anyone lucky enough to see him play during that brief period before he became the Most Famous Guitarist in the World is unlikely to forget it.

Hendrix’s rise is usually dated from September 1966, when Chas Chandler brought him to England, but the natural stages by which his playing developed don’t fall quite as neatly into line. It’s clear from the descriptions of fellow American musicians like Mike Bloomfield and John Hammond that everything was already in place by Jimi’s last six months in Greenwich Village, where he worked under the name of Jimmy James & The Blue Flames. Mike Bloomfield was guitarist with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and a session-player on various Dylan recordings including ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ and Like A Rolling Stone. He considered himself to be the top US guitar player, bar none, until he heard Hendrix.

Mike Bloomfield. I was the hot-shot guitarist on the block. I thought I was it. I’d never heard of Hendrix. Then someone said, ‘You gotta see the guitar player with John Hammond’. I went straight across the street and saw him. Hendrix knew who I was and that day, in front of me eyes, he burned me to death. I didn’t even get my guitar out. H-bombs were going off, guided missiles were flying – I can’t tell you the sounds he was getting out his instrument. He was getting every sound I was ever to hear him get, right there in that room with a Stratocaster, a (Fender) Twin, a Maestro fuzztone and that was all. He just got right up in my face and I didn’t want to pick up a guitar for the next year.

Hendrix arrived in England in September 1966, and started playing shows the following month. By December he was gigging regularly and between January and March 1967 the Experience played about 20 club dates per month. By April ’67, the second single Purple Haze was in the charts and Hendrix had moved on from small clubs into theatres. Bashing round the country on the bill of a (singularly ill-matched) package-tour, Hendrix was well on the way to becoming public property. The secret was out of the bag: he was a major star in waiting, about to be unleashed before the world at the Monterey festival in June.

Apart from the pleasure of being in on the secret, there was something very special about those early shows, when you could stand a few feet away and watch Jimi playing to a couple of hundred club-goers. Combining the last months in America and the early days in England, it looks as though this final stage in his apprenticeship ran from around April 1966 till the end of March 1967. His skills were all in place but his fame had not yet grown so large that it came between you and what you were seeing.

When I saw him first, in February ’67, he wasn’t really known outside London. I’d heard Hey Joe on the radio -- and that was it. I had no expectations, no preconceptions. A school friend asked if I wanted to “go down the Locarno and see this American guitarist who plays with his teeth.” I said no -- but I went anyway.

The set contained only a few originals: Stone Free, Foxy Lady, Can You See Me and a song you might not expect so early, Third Stone from the Sun. These were mixed in with the material he’d been playing back in Greenwich Village at The Café Wha? -- Hey Joe (a cowboy song that Jimi made his own) straightforward covers of Rock Me Baby, Wild Thing and even the odd soul standard like Midnight Hour.

The best thing about these shows was the amount of fun Hendrix had playing them. He could handle the material in his sleep. He knew he could murder any guitarist in England. The lack of pressure, and the sense that something big was just about to happen for him produced ideal conditions to take risks, to kick the material out of shape and -- in a big word of the day -- 'loon' around with it. I saw Hendrix half a dozen times after he became a big star but I never saw him so completely carefree, or having such fun.

At the other end of the spectrum was the miserable Isle of Wight show in the summer of 1970, just a couple of weeks before he died. Hendrix was such an open, unprotected performer you always got a sense of how he was feeling on any given night from the sound he produced. That may sound like a fundamental requirement of any performer but believe me, it isn't. Only the very best are capable of eliminating the barrier between themselves and their performance, and of them, only a few are willing to go out into the ring without the safety of a rehearsed, pre-planned show. And that’s just as well: few performers are interesting enough to hold your attention for an hour with little more than extemporization.

At the Isle of Wight everything was wrong. Hendrix’s tone sounded edgy and brittle: his timing, usually so tight you never thought about it, was off. But the surest sign that something was wrong could be heard in his feedback. Instead of the usual rich, harmonically-pleasing notes an octave or an octave-and-a-half above the played note, his amps were producing discordant shrieks at random pitches -- more like a microphone feeding-back than a guitar. At most other times, Hendrix's use and control of feedback was supremely musical. He used discord and atonality but he never let them use him. At the Isle of Wight however, it slipped away from him -- and worse, you could feel it slipping away. Staying up four nights on Methedrine can really ruin your timing.

* * *

Hendrix had fairly relaxed ideas about contractual law -- though that was nothing new. In the musicbiz of the 50’s and early-60’s, songwriters would traditionally sell a song to 3 or 4 different publishers on the same day if they thought they had a winner. The trick was to get it sold quick. In the days when he had nothing to lose, Jimi treated contracts more like receipts than binding agreements. If somebody offered you $20 for a signature, you signed. Course you did. And signed an identical document promising everything to someone else the next day, if they offered money, too.

One such contract was offered by producer Ed Chalpin, whom Hendrix met through a Kansas-born singer/guitarist named Curtis Knight. Hendrix spent the summer of 1965 scuffling for gigs and sessions around New York and bumped into Curtis Knight at a time when he was short of a guitar. (Jimi was always losing or pawning instruments.) Knight saw Hendrix’s potential, lent him a guitar and immediately added him to his band, The Squires, who played regular dates around the bars and clubs of New York and Jersey. Curtis Knight was ambitious. A better hustler than he was singer, he figured that the new guitarist would also make an impression in the studio, so he approached Ed Chalpin who ran Studio 76, on Broadway and 51st.

Chalpin quickly spotted Hendrix’s potential and signed him up to his production company, PPX. This agreement contracted Hendrix to produce and play exclusively for PPX for 3 years, in return for one dollar. Chalpin seems to have seen this as a pretty good break for the young Jimmy Hendrix …

Ed Chalpin. In almost 40 years of my career as a producer and manager I have, at most, taken eight acts under contract. They had to be something special. One of them was Jimmy Hendrix. Jimmy was to sing play and arrange for me exclusively. The contract was signed in the Hotel America on the night of 15th October 1965. At that time it was usual to insert the clause ‘For one dollar and other good and valuable consideration’ in contracts.

Tracks 1-10 of this album come from two studio sessions in late 1965, recorded soon after Jimmy signed to Chalpin. They’re mostly originals, written by Curtis Knight or other players on the sessions -- though some originals are more ‘original’ than others, as you’ll see when you play the ‘protest’ song, How Would You Feel. Hendrix’s guitar line shows that he was familiar with Mike Bloomfield’s work on Like A Rolling Stone.

Both How Would You Feel b/w Welcome Home and Hornets Nest b/w Knock Yourself Out were released as US singles in early 1966; the former was an attempt to crack the topical protest market, while Welcome Home bears more than a trace of Marvin Gaye's Can I Get A Witness.

Knock Yourself Out is a solid instrumental built over the same chord progression as Lee Dorsey's Get Out My Life Woman, and owes something to the sort of guitar showcase written by Earl King or Freddy King. If the Experience had ever organized the much talked-about session with Keith Emerson, it might have sounded like this. Hendrix’s guitar playing is tasty. He starts off in Booker T territory but moves along briskly: Steve Cropper never played that many notes. The ease with which Hendrix mixes set pieces from the instrumental blues guitar repertoire with stunts borrowed from surf-instrumentals makes it easy to understand why Third Stone From The Sun was one of his earliest compositions for the Experience.

Guitar players, and serious Hendrix enthusiasts will be interested in the rhythm guitar parts. We all know Jimi's lead lines backwards, but the key to his musical personality – and the reason he was such an effective songwriter -- is his strength as an accompanying guitarist. Where most guitarists are chiefly concerned with laying decorative lines on top of a song, Hendrix’s thinking is structural: his guitar parts work away inside a song, creating countermelodies and gospel-styled call and responses. Gotta Have A New Dress is a case in point. The solo is more or less what one would expect from 1965 Jimi, but the intro, and the guitar responses to the title line are a model of crisp R&B phrasing: tight, compact and melodic.

So here’s the 22 year-old Jimi Hendrix, working his first sessions as a ‘signed’ musician and arranger. Play the album and marvel at how much guitar-player you could get for $1 in the New York City of 1965!